GLOBAL COMMODITIES

Soy

Soy in Brazil

The 1960s marked the beginning of soybean production in Brazil. The planting of soybeans during this period appears mainly in the south of Brazil linked to the culture of other grains, such as beans and rice. From the 1970s onwards, the government through the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) invested heavily in research to improve and adapt the species to warmer climates. Large investments in genetic research, in industrial complexes, infrastructure and colonization projects in the center west of Brazil took soy to the Brazilian Savannah (named Cerrado) during the 1980s and the 1990s. The expansion of soy in the Cerrado was developed along with the installation of large agro-industrial complexes by large corporations. In the Cerrado, soy production was concentrated mainly on medium and large properties, unlike in the southern region of the country, where smallholders farmers participate in the value chain.

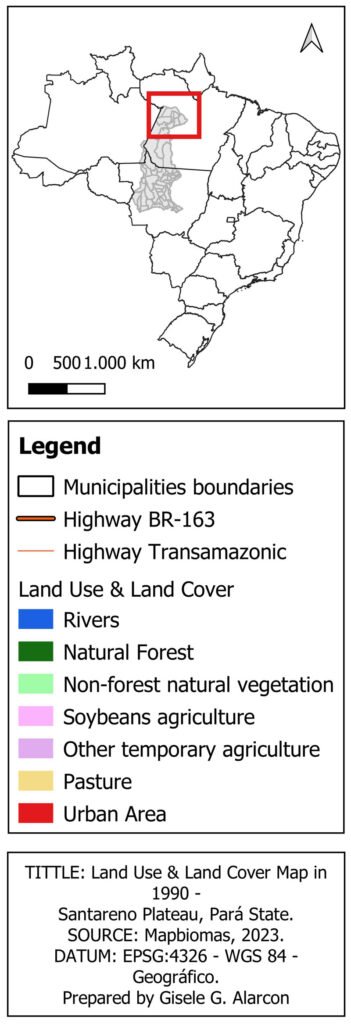

In the late 1980s and 1990s, EMBRAPA started the first experimental soy planting stations in the Amazon region, in the states of Rondônia, Pará and Amazonas. The Pará State Agricultural Policy Operational Plan carried out in the same period resulted in the creation of several Agricultural Development Poles in the state. In Santarém, one of the stations of the Agroindustrial and Agroforestry Pole of West Pará was responsible for promoting the production of soy in the Santareno Plateau region.

Several studies point out that the cultivation of the soy culture in the Tapajós Region initially took place in degraded pasture areas, but also in areas of native forest. The practice of deforestation, expulsion of smallholders farmers and other traditional communities and land grabbing marked the arrival of soy in the region. In the early 2000s, the installation of the Cargill port in Santarém and the indication of the BR-163 paving were decisive factors for the rapid expansion of soy throughout the Santareno Plateau.

Land Use and Land Cover dynamic at the Santareno Plateau between 1998 and 2021, Tapajós Region, Brazil.

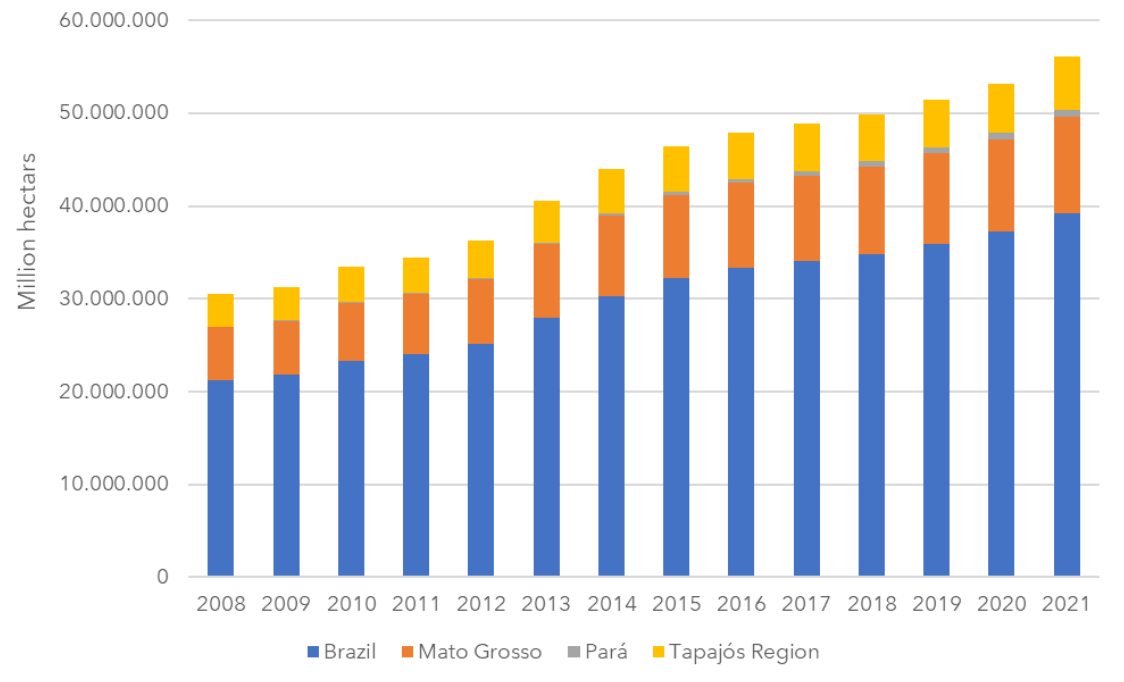

For the whole Tapajós Region, between 2008 and 2021, the area destined to soy planting grew 60%, jumping from 3.5 million hectares to 5.7 million hectares. In 2021 the region produced approximately 20 million tons of soy (IBGE, 2023).

According to ABIOVE (Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries), in 2022, 61% of the soybeans produced in Brazil were exported, 52% of the soy meal and 26% of the soy oil. The main importing economic blocks were China, followed by Asian countries (except China) and the European Union. The EU represents 16% of the soy import market and 44% of the soy meal import market, constituting the main trading partner for this soy-derived product. The participation of the ports from the Arco Norte in the total soy’ exportation has increased in the last decade. In 2022 it represented 38% of the origin of the ports exporting soy from Brazil, with emphasis on São Luis (Maranhão), Barcarena and Santarém (Pará) and Manaus (Amazonas). Approximately 60% of the soy exported from the ports of Santarém and Itaituba, both in the Tapajós River, are to the European Union, Russia and other European countries as England.

In the last 4 years, soy has been the main cargo transported inland (rivers) in Brazil, representing about 1/4 of the total. Soy, corn and bauxite together represent 50% of the cargo transported in Brazilian rivers (ANTAQ, 2023). The logistics of transporting minerals for exportation, such as bauxite and steel, has been used jointly by corporations of the agribusiness sector.

The expansion of soy plantation and the infrastructure associated with it for production, storage, processing (in the case of soy meal and oil), transport and exportation has led to a series of human rights violations in communities in the Tapajós Region. Contamination by pesticides has drastically altered forms of agroecological production and forest management since they cause the death of pollinators and the increase of pests in pesticide-free zones. Another impact of great relevance consists of land grabbing by large farmers from the south of the country, the expulsion of smallholders farmers from Agrarian Reform settlements and illegal production within indigenous and other traditional communities’ territories. These land conflicts have led to persecution of leaders, attacks and murders.