GOVERNANCE & PERVERSE CONNECTIONS

Climate Change Adaptation

Tapajós Region, Brazil

The Paris Agreement came into force in 2016 and established that each country member of the agreement would propose greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets, based on the so-called Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (iNDC) (UNFCCC, 2018). The Brazilian National Congress approved the ratification of the agreement in September 2016, transforming the iNDC into a mandatory commitment.

With the ratification of the Paris Agreement, Brazil committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by 37% by 2025 and 43% by 2030, both compared to 2005 emissions. In the same year the government prepared the National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (PNA) involving 55 public policies, plans and programs in different sectors. To achieve the emission reduction target, the country committed to increasing the share of sustainable bioenergy in its energy matrix, restore and reforest 12 million hectares of forests, and achieve an estimated 45% share of renewable energy in the composition of the energy matrix in 2030.

The Brazilian NDCs have had 3 updated versions since the original publication. The second update published in 2022 represented a step back on the reduction targets as it allowed an increase of approximately 400 million tons more of GHG emissions (WRI, 2022).

However, on its third updated version, in September 2023, at the Climate Ambition Summit, organized by the United Nations (UN) in New York, the Brazilian government has restored its original goals of having an emissions limit of 1.32 GtCO2e – consistent with a 48.4% reduction by 2025, and 1.20 GtCO2e – consistent with a 53.1% reduction by 2030, compared to 2005 emissions. Furthermore, Brazil reiterated its commitment to achieving net neutral emissions by 2050, that is, everything the country emits it must be compensated with carbon capture sources, such as forest planting, biome recovery or other technologies (MMA, 2023).

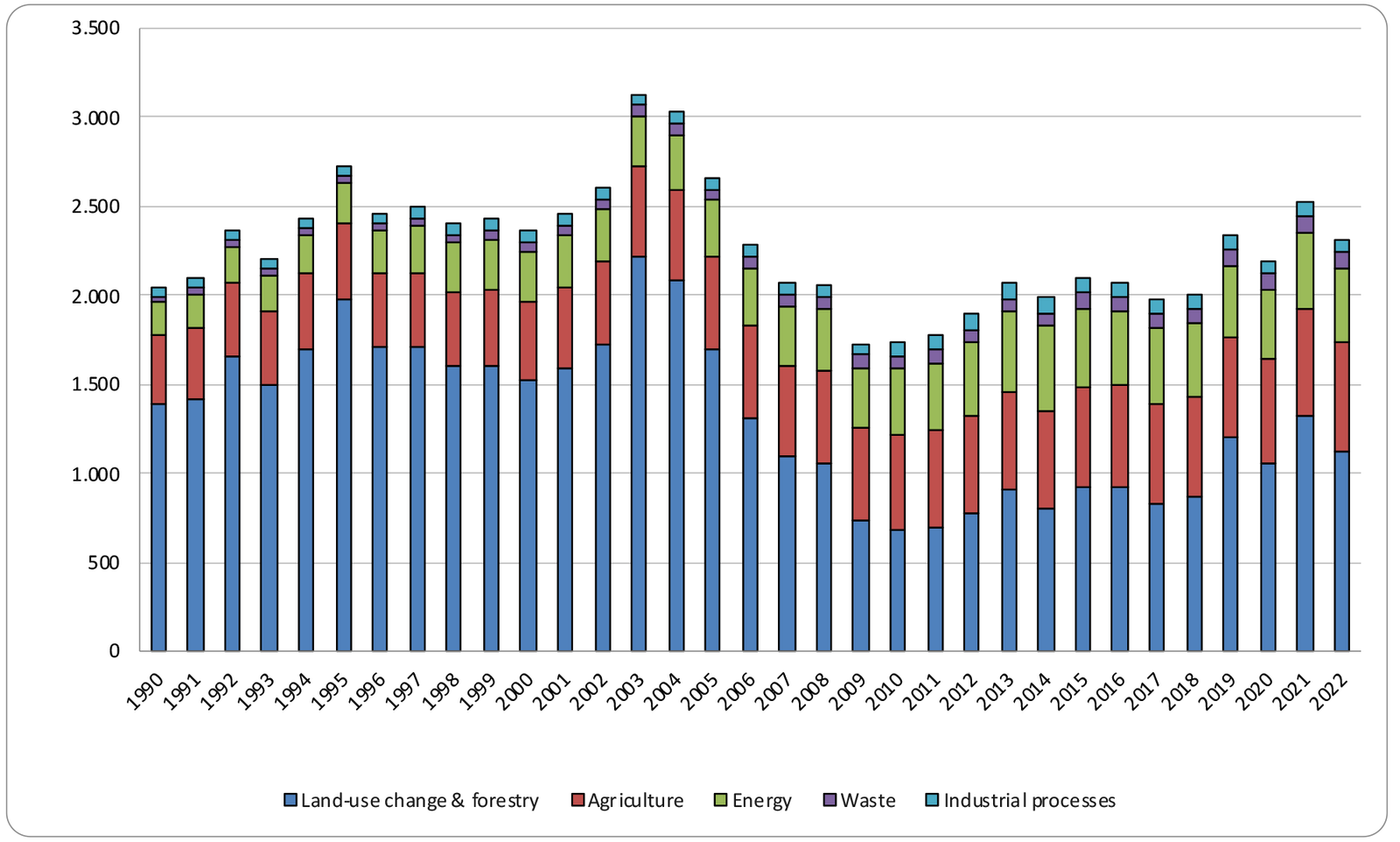

Almost half of Brazilian emissions come from Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LUCF) (48%), followed by the Agriculture Sector (26%) and the Energy sector (17%). Pará and Mato Grosso states lead the ranking on LULUCF emissions (SEEG, 2023).

In the last four years the weakening of environmental policies and the dismantling of environmental inspection bodies, associated with the increase of land invasion and violation of the rights of traditional communities resulted in a significant increase in deforestation, especially in the Amazon region, but also in the Cerrado and Pantanal. However, with the change of government and resumption of environmental policies, between January and August 2023 a 48% reduction in deforestation rates was recorded through the new phase of the PPCDAM (Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Amazon). Deforestation is imbricated with the agribusiness sector, as much of the forest loss is for cattle raising and soybean production in the Amazon.

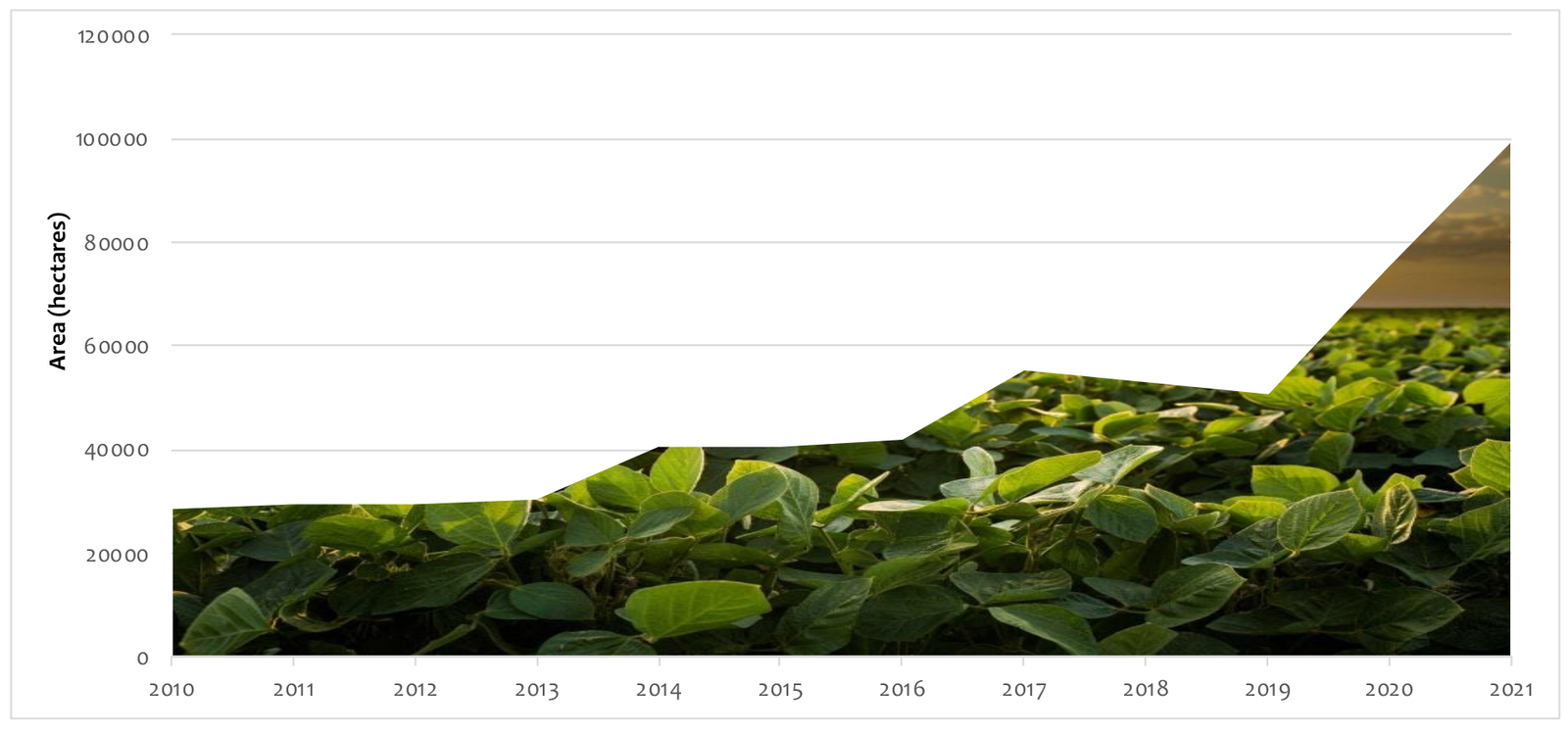

In the Tapajós Region the area (ha) of soybean planted specifically in the Santareno Plateau, Transamazonic and BR-163, in Pará, increased 254% between 2008 and 2022. In the same pace, cattle herds increased from 1,4 million to 2,2 in the same period (IBGE, 2023). Although most of the soybean area is not advancing in the forest, it pushes the expansion of pasture into the forest land.

While the state encourages and subsidizes the implementation of infrastructure to expand the production of these and other commodities, such as palm oil, it seeks to demonstrate commitment to the emissions reduction targets of the Paris Agreement. As an example, recently Helder Barbalho, the governor of Pará signed an agreement to join the Race to Zero campaign, a global initiative which aims to bring together leaders to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The goal must be achieved through actions to decarbonization, attracting investments for sustainable businesses and creating green jobs.

The Growth Acceleration Program (PAC, acronym in Portuguese, the main public investment program of the Lula government) is forecasting investments of almost R$39 billion in Pará. The PAC is planning 18 transport infrastructure projects, which include paving and improvements on BR-163, the completion of the bridge over the Araguaia River (BR-153) and the paving and construction of bridges on sections of BR-230 (Transamazonic road). In the railway sector, investments are planned in the Carajás Railway and the preparation of studies for the concession of EF-170, to Ferrogrão. There are also investments planned in the ports of Barcarena, Belém, Santarém and Vila do Conde, and in waterways with the aim of improving transport through the State’s rivers.

All these investments aim to attend to the demands of infrastructure for commodities transportation and exportation, consolidating the region as a north corridor of raw materials low to the global north to the detriment of the forest, sociobiodiversity and the amazonidas people. This model drastically clashes with the targets of emissions reduction and a low-carbon economy.

Putumayo, Colombia

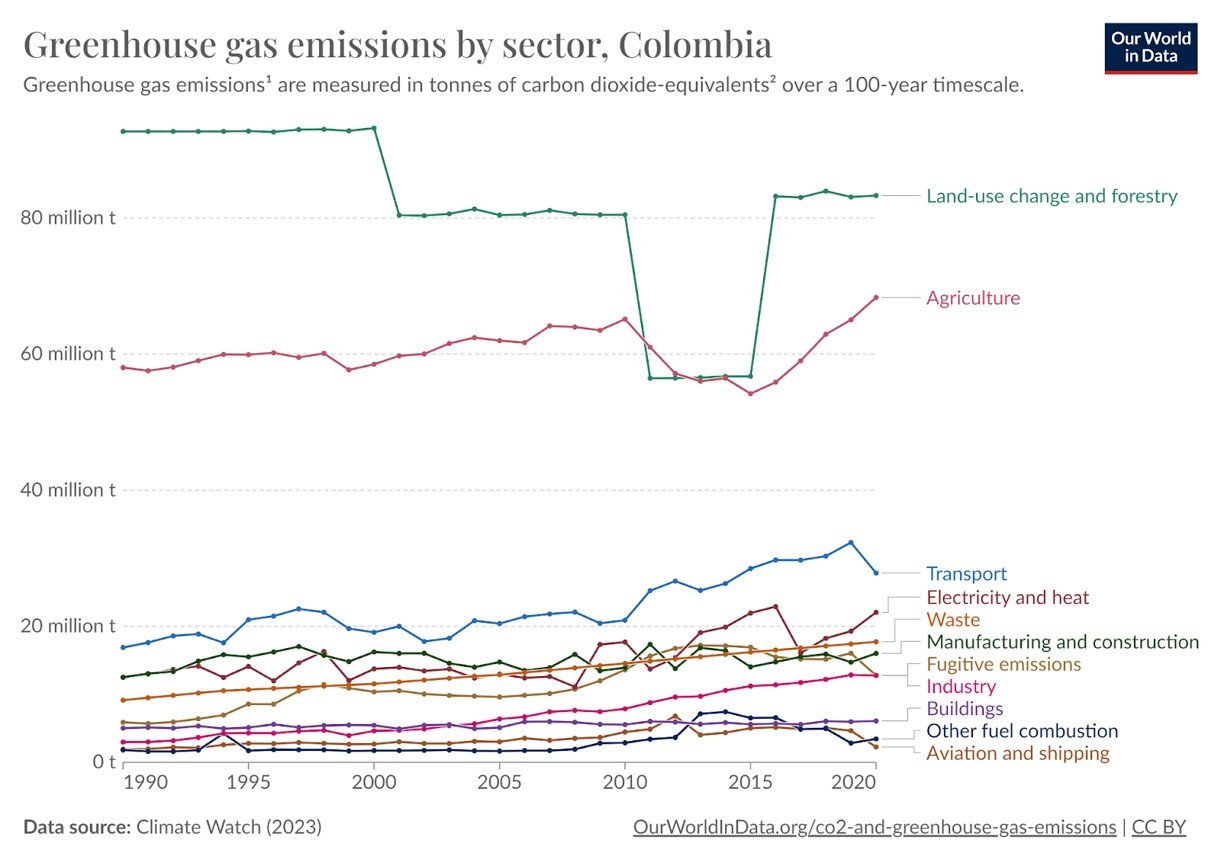

Colombia is a signatory of the Paris agreement, which it ratified in 2018. Moreover, Colombia has committed to reducing carbon emissions and the revised NDCs include a more ambitious mitigation target of 169.4 MtCO2eq by 2030, equivalent to a 51% reduction in emissions from a revised 2030 reference scenario (UNDP, 2023). In global comparison, the consumption based emissions per capita are rather low with 2 tons per person in 2021 (Global Carbon Budget, 2023). Nonetheless, a main challenge remains land-use change and forestry related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which represents the sector generating the largest share of GHGs in Colombia (Our World in Data, 2023).

Colombia has seen a substantial surge in deforestation over the last decade driven by an expansion of industrial agriculture and palm-oil, of cattle ranching activities in the Amazon frontier region, and of illicit crops and infrastructure projects. Particularly after the Peace Agreement between the government of Colombia and the FARC-EP guerilla, deforestation soared in areas previously under the control of the guerilla groups. Exploiting the void of authority and lack of state control, and in expectation of obtaining legal land titles, powerful landowners and cattle ranchers expanded their activities into forested areas. Most of the deforestation took place along the north-western fringes of the Amazon region, including the Putumayo department.

Indonesia

The Indonesian government has set targets of reducing carbon emissions while at the same time promoting development projects that potentially hamper its fulfillment. Based on the Enhanced Nationally Determined Contribution (ENDC) released in 2022, the country is targeting to cut down carbon emissions by 1,953 MTonCO2-eq, which will be 31.89% lower compared to the business-as-usual scenario greenhouse gas (GHG) emission of 2,869 MTonCO2-eq in 2030. It also says that the country will be able to reach a reduction of up to 43.2%, conditional to international support for finance, technology transfer and development, and capacity building. The ENDC is an update to the NDC target announced in 2016, in which the objective was 29% for the unconditional scenario and 41% for the conditional scenario. In addition, the government estimates that the country will reach the peak GHG emission in 2030 at 1.2 GtCO2-eq, after which it will decline and reach net-zero emissions by 2060.

Emission reduction from forestry and other land uses (FOLU) is expected to contribute the most to the carbon net sink. Policies are in place to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, increase the carbon sequestration capacity of natural forests, increase carbon sequestration of land systems, and reduce emissions from fires and peat decomposition (Kementerian, 2022). The backbone of the target is REDD+. In 2015, the government submitted the Forest Reference Emission Level (FREL), which was set at 0.568 GtCO2-eq with a reference to the 1990-2012 period to evaluate emissions during 2013-2020. In 2022, it submitted the second FREL as a benchmark to evaluate emission levels during the 2021-2030 period. Among important updates is that the proposed new benchmark takes into account deforestation, forest degradation and enhancement of forest carbon stock, decomposition of peat, fires (peat and minerals) in areas experiencing deforestation or forest degradation, and emissions from conversion of mangrove forests into cultivated areas. It also calculated carbon pool pools above-ground biomass, below-ground biomass, dead wood, litter, and soil. Indonesia has also been pushing for the development of carbon capture storage (CCS), in which state-owned enterprise Pertamina is expecting to collaborate with international companies (Pertamina, 2023). In September 2023, the country officially launched the carbon exchange, branded as the IDXCarbon. The carbon exchange directly connects to a registry system managed by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry to prevent double counting.

In the energy sector, however, Indonesia has taken a middle-of-the-road approach, as it maintains a certain level of support for the fossil fuel industry. Based on the ENDC target, emission reduction from the energy sector is far from ambitious, as seen from the estimated GHG output in both unconditional and conditional scenarios. This target is set against the backdrop that the government has issued policies promoting the utilization of renewable energy, cutting down fuel subsidies, requiring a mix of bio content into diesel fuel, and deploying electric vehicles. Also, in 2022, a presidential regulation was introduced to prohibit the development of new coal power plants, except those that had been approved before the order became effective. In 2022, Indonesia also secured the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), which is expected to deploy $20 billion of public and private financing towards decarbonization. Under the initial plan, the JETP aims to limit carbon emissions from the power sector to 290 MTonCO2-eq by 2030, set renewable energy’s contribution to 34% in electricity generation, and reach a net zero emission in the sector by 2050 (UNDP, n.d.). Under its comprehensive plan, JETP (2023) targets to early retire 1.7 GW of coal plants by 2040, reach a peak of on-grid power sector emission by 2030, emission level of no more than 250 MTonCO2-eq by 2030, renewable share in energy generation of 44% by 2030, and achieve a net-zero emission n the power sector by 2050.

Aside from the electricity sector, mitigation efforts under the ENDC also cover the upstream extraction business. The ENDC is looking at a post-mine reclamation of 81,069 hectares under the unconditional scenario of emission reduction from the energy sector and more undedicated targets under the conditional scenario. Meanwhile, in the IPPU sector, mitigation efforts planned include the implementation of landfill gas (LFG) recovery, treatment of industrial waste, as well as utilization of waste as an energy source through the Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF) and biomass power plants.

During fieldwork conducted throughout 2020-2023, our team attempts to understand how the dynamics of supply and value chain in the tin mining and oil palm plantation also influence climate change. From interviews and discussions with key stakeholders in the two sectors, we conclude that there are a lot of practices that raise our concerns related to emission reduction targets.

In the tin sector, we understand that smelting and refining will continuously need coal to fuel the furnaces for 24/7. The use of solar panels has been progressing in Bangka. However, to our understanding, this remains limited to in-office utilization and electric vehicles. On the one hand, the industrial use of coal to power furnaces reflects the target of emission reduction from the energy sector, which will unlikely subside to zero even after the country reaches the net zero emission period. On the other hand, this also means that fossil-based sources will become a “strategic” material that supports the country’s downstream policy, or hilirisasi, in the mining sector. In 2009, Indonesia introduced the Mining Law, requiring all mineral products to be processed before export. In the implementation, this policy translates into a ban on raw material exports and minimum purity or refining levels. Objectives of this policy include encouraging domestic downstream policy, industrialisation, and preservation of certain commodities for national utilization.

Apart from the electricity issue, we also understand that tin smelting and refining require additional elements, such as aluminum and zinc, to reach certain purity levels. From our visit to a smelting facility in Bangka, the company recycles cans of soft drinks to get the necessary elements that later are mixed to get tins of above 90% purity levels. While recycling displays a circular movement of material usage, regulations on waste management are in need of improvement as part of the national decarbonisation agenda in the mining sector. One issue is related to the uncontrolled radioactive-contained waste from the smelting and refining activities.

Tin mining in Bangka Belitung Province has now expanded massively into the onshore areas, which are believed to have bigger deposits. With the expansion, marine ecosystems and fisheries are threatened. Under the current ENDC, the government of Indonesia has set strategies for coastal zone protection as part of an attempt to establish and maintain ecosystem and landscape resilience. Nevertheless, the strategy and action still focus on pollution control (especially plastic) and the mangrove ecosystem. There remains a lack of attention to the blue carbon development to anticipate onshore mining expansion such as tin.

Biodiversity Conservation

The main international agreement on the protection of biodiversity and natural ecosystems are the Aichi goals, proposed within the scope of the 10th Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The Convention’s signatory countries adapted their national goals to the CBD’s goals and established their National Biodiversity Strategies and Plans for the period 2011-2022. The Aichi goals followed the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity developed under the period 2002-2010, which hardly got advances on the goals proposed.

In this item we discuss the progress of the Aichi goals in the three countries that are part of the global tropical belt, seeking to debate how the Aichi goals are affected by the global agri-food model based on the production and exportation of commodities from the tropical belt to the global north .

Tapajós Region, Brazil

Brazil ratified the CBD in 1994 and enacted the National Biodiversity Policy in 2002. In 2011, the federal government, in partnership with several non-governmental organizations, researchers, representatives of indigenous people and traditional communities, and the private sector, carried out an initiative known as Dialogues on Biodiversity: building Brazilian goals for 2020. This initiative, which included a series of workshops, culminated in the preparation of national biodiversity targets for 2020 within the scope of the Strategic Biodiversity Plan 2011-2020. The goals and subgoals proposed within the scope of these workshops were opened for online public consultation in order to consolidate the final goals considering the suggestions and criticisms of the consultation.

In 2013 the CONABIO Resolution nº 06 regulated the national goals for biodiversity conservation in relation to the Aichi Goals. That same year, a voluntary network of organizations from different sectors of society, PanelBio, was formed, whose mission is to promote the achievement of national goals. And, in 2017 the revision of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plans (NBSAP) was accomplished and published. The national biodiversity goals for the period 2011-2020 were divided into 5 main objectives, namely:

- Address the root causes of biodiversity loss

- Reduce direct pressures on biodiversity and disrupt sustainable use

- Improve the biodiversity situation by protecting ecosystems, species and genetic diversity

- Increase the benefits of biodiversity and ecosystem services for all

- Increase implementation through participatory planning, knowledge management and capacity building

The construction of the national biodiversity goals and of the NBSAP counted with multiple participative methods to represent the different interests of Brazilian society. Although its methodology was considered a reference for other countries, some goals clash directly with national development projects and investments.

In relation to agriculture development and commodities production and exportation, the biodiversity national targets nº 3 and nº 5 are in contradiction with what was observed in practice in the period 2011 to 2020.

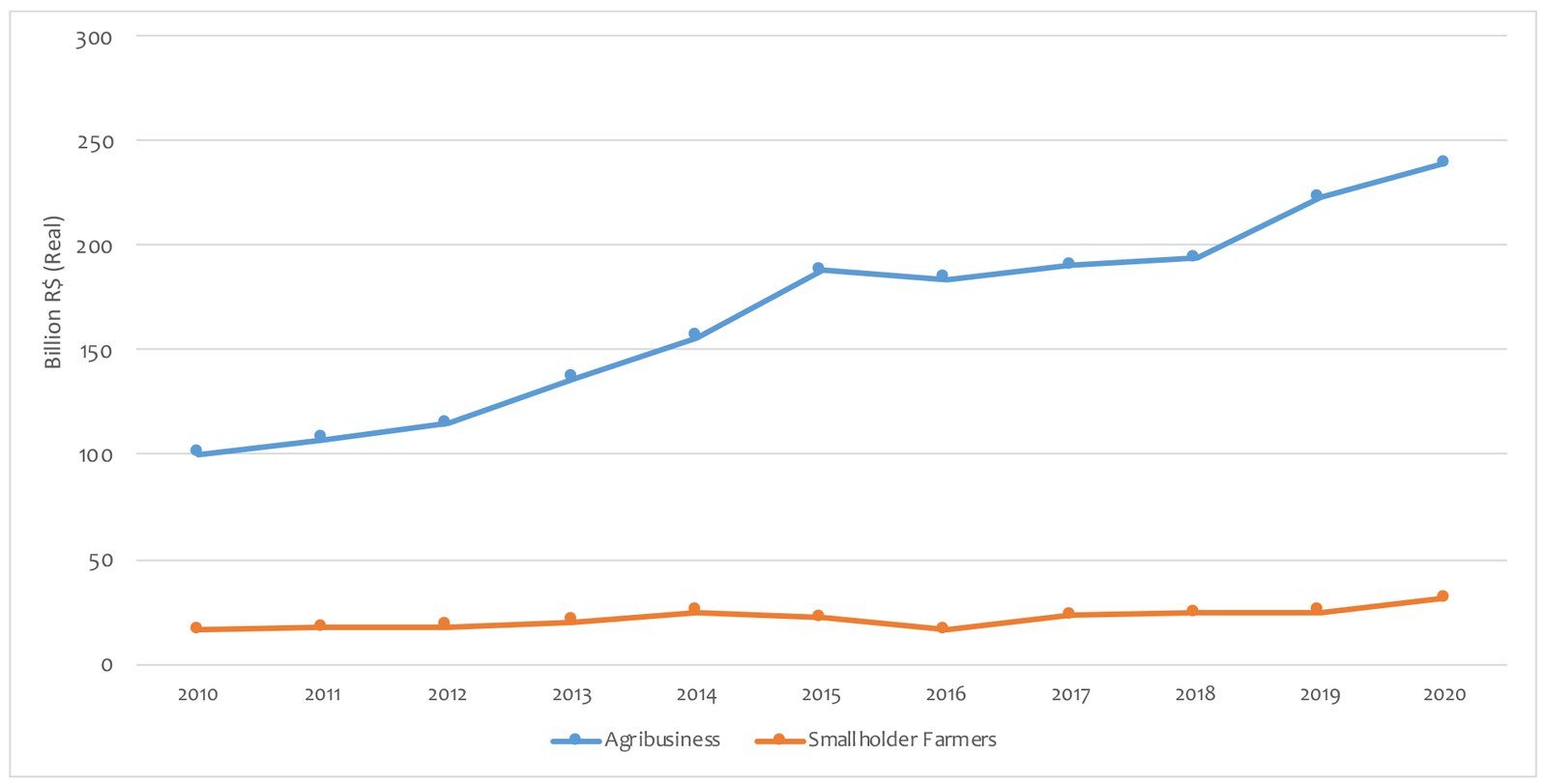

The national goal nº 3 aimed at reducing perverse subsidies that may affect biodiversity, in order to minimize negative impacts. On the other hand, it proposed (not quantitatively) the design and application of positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in accordance with the CBD. Globally, according to the Global Biodiversity Outlook, subsidies of around US$500 billion boosted activities that threaten ecosystems and biological diversity. According to the network Climate Land Ambitions and Rights Alliance, direct and indirect incentives and subsidies for agriculture in areas with high levels of deforestation like the Paraguayan Chaco, the Brazilian Cerrado and Northern Argentina are harming biodiversity, forests and traditional communities and indigenous people rights, by dispossessing them from their lands and forests. On the other hand, large agribusinesses receive all of the economic benefits. In Brazil, rural credit for smallholder farmers & traditional communities compared to business agriculture have historically had a huge difference. The increase of credit availability for agribusiness rose 140% in one decade, jumping from R$ 100 billion reais (US $ 20.2 billion) to R$ 239 billion (US$ 48.1 billion).

In addition to the high availability of rural credit at low interest rates and privileged debt payment conditions, exemptions and tax reductions in the sale, industrialization, importation and use of pesticides in Brazil is huge. A study developed by FioCruz Foundation estimated, in 2017, that these positive incentives to fertilizers and pesticides in Brazil represented at that time a total of R$8.16 billion less in government coffers. Currently, the granting of tax exemptions to pesticides is being questioned in the Federal Supreme Court (STF). The 60% reduction in the ICMS (Tax on Circulation of Goods and Services Interstate and Intermunicipal Transportation and Communication Services) tax for pesticides on interstate and in internal operations are being questioned, as well as the granting of total exemption from taxes on industrialized products (IPI) for pesticides.

Another important national biodiversity goal is the nº 5 that is in complete friction with business agriculture expansion for commodities exportation. The goal nº 5 proposed a 50% reduction in the loss of natural ecosystems and the reduction of degradation and fragmentation of vegetation in all Brazilian terrestrial biomes between 2010 and 2020. Although in general terms the loss of natural ecosystems in the Brazilian biomes declined along this period, in some biomes the rates started to rise again after 2017 with the policy of environmental destruction carried out by the government of Jair Bolsonaro.

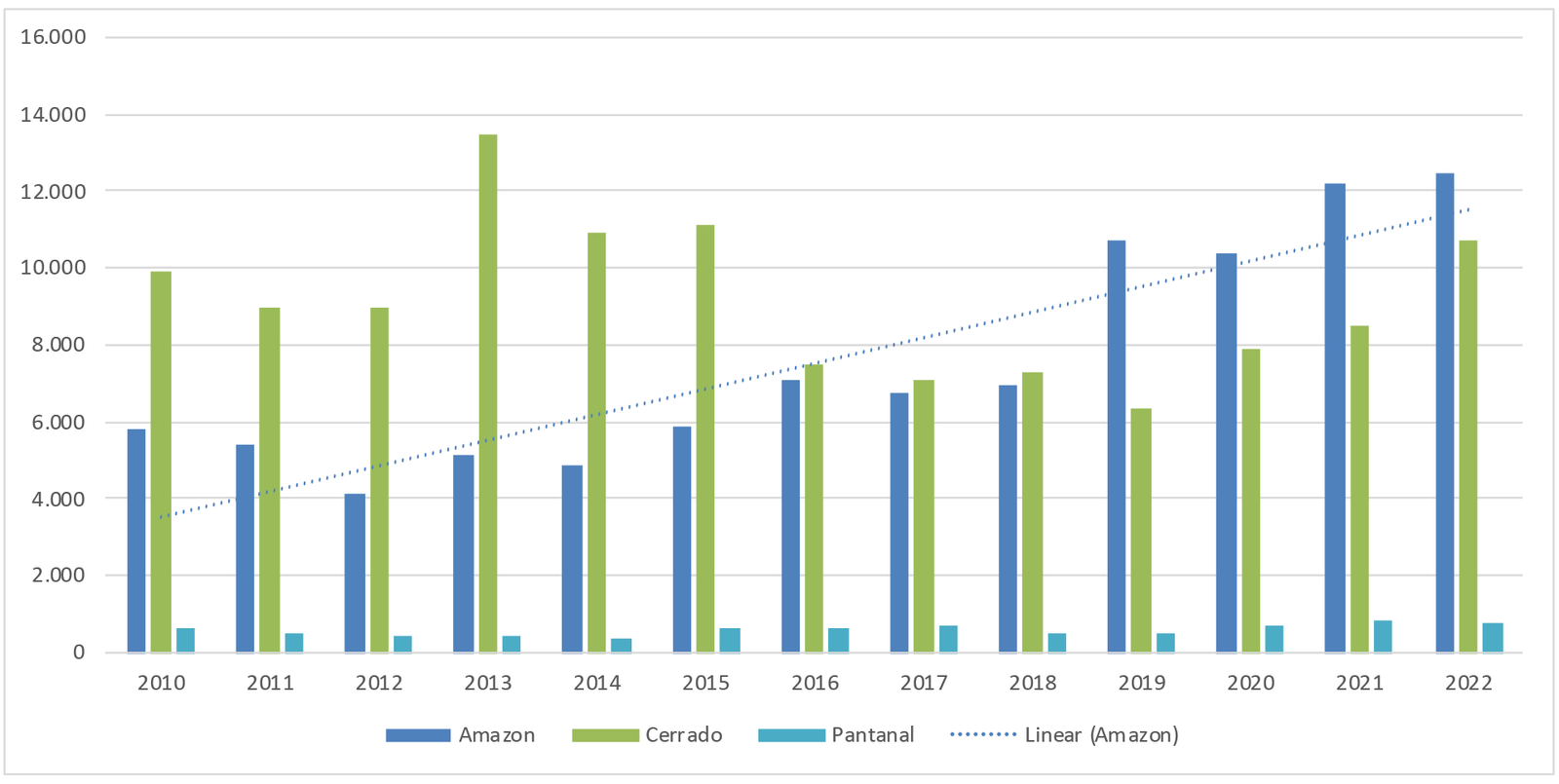

For the Amazon, deforestation rate increased 114% from 2010 to 2022. In the case of Pantanal, deforestation rate rose 19% in the same period and in the Cerrado, the heart of soybean plantation in Brazil, deforestation rate increased approximately 10%. In the Tapajós region, only in the Santareno Plateau, soybean plantation area increased 247%, jumping from 28 thousand hectares in 2010 to 99 thousand hectares in 2021. Expansion of soybean plantation in the Amazon has been mainly over degraded areas (pasture lands), but it also takes place on recent deforested areas as reported by the Guardian (2022). As soybeans occupy pasture areas, deforestation and land grabbing expands under public forests and those of indigenous peoples and traditional communities, creating a circle of destruction. In this circle, soy goes into pasture and pasture into the forest, after a few years of pasture and the regularization of the land, the regularized private property is purchased by soybean producers, generating pressure for new pasture areas (Amazonia Latitute, 2021). The two main drivers of deforestation in Brazil are entirely related to the production of commodities for exportation, cattle and soybeans (TRASE, 2022).

Putumayo, Colombia

Colombia is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. Due to its geographic location and its great variety of biomes along the Pacific and Caribbean coastlines, the Andean Cordilleras and valleys, the Eastern plains of the Orinoquia savannahs, and Amazonian forests.

Colombia is a signatory of the Convention on Biological Diversity and will host the next CBD COP in 2024. As of June 2021 the National System of Protected Areas (SINAP) of Colombia has expanded its coverage to 16.61% of the country’s terrestrial (16.61%) and 13.40% of its marine territory, which means it exceeded the Aichi target to conserve 10% of the world´s marine and coastal areas, but falls short on the target of protecting 17% of its terrestrial area (CBD, 2021).

Nonetheless, a large portion (almost 50% in the Amazon region) of Colombia’s land area is legally designated as Indigenous and afro-colombian territories, which is a right of collective land ownership provided under the Constitution (Constitution of Colombia, 1991). While some of these areas may overlap with protected areas, the majority is outside of protected areas, but provides a certain level of protection for ecosystems and biodiversity.

However, despite the expansion of protected areas and the legal land titles that indigenous groups and afro-colombian communities hold, the expansion of the commodity frontier does not respect these boundaries. Illegal land grabbing has been reported to take place within national parks and is also encroaching into indigenous territories, resulting in violent displacements and conflicts[1] (Volckhausen, 2019)[2]. Apart from these social consequences, the land use change and deforestation caused by expanding cattle ranching, mining, and coca plantation also leads to a decline in populations of wild species, ecosystem fragmentation and a loss of important biological ecological corridors connecting the Andean Cordillera with the Amazonian lowlands. The threat to the ecological connectivity is a particular concern in the Putumayo and also affects the cultural and spiritual connectivity that is embedded in the worldview of many indigenous groups living in the Andean-Amazon region (Samper and Krause, 2024)[3].

[1]

Volckhausen, T. (2019). Land grabbing, cattle ranching ravage Colombian Amazon after FARC demobilization. Mongabay. Retrieved July 20 from. Check here.

[2]

Samper, J. A., & Krause, T. (2024). “We fight to the end”: On the violence against social leaders and territorial defenders during the post-peace agreement period and its political ecological implications in the Putumayo, Colombia. World Development, 177, 106559. Check here.

Ruette-Orihuela, K., Gough, K. V., Vélez-Torres, I., & Martínez Terreros, C. P. (2023). Necropolitics, peacebuilding and racialized violence: The elimination of indigenous leaders in Colombia. Political Geography, 105, 102934. Check here.

Murillo-Sandoval, P. J., Kilbride, J., Tellman, E., Wrathall, D., Van Den Hoek, J., & Kennedy, R. E. (2023). The post-conflict expansion of coca farming and illicit cattle ranching in Colombia. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 1965. Check here.

Vanegas-Cubillos, M., Sylvester, J., Villarino, E., Pérez-Marulanda, L., Ganzenmüller, R., Löhr, K., Bonatti, M., & Castro-Nunez, A. (2022). Forest cover changes and public policy: A literature review for post-conflict Colombia. Land Use Policy, 114, 105981. Check here.

Salazar, A., Sanchez, A., Dukes, J. S., Salazar, J. F., Clerici, N., Lasso, E., Sánchez-Pacheco, S. J., Rendón, Á. M., Villegas, J. C., Sierra, C. A., Poveda, G., Quesada, B., Uribe, M. R., Rodríguez-Buriticá, S., Ungar, P., Pulido-Santacruz, P., Ruiz-Morato, N., & Arias, P. A. (2022). Peace and the environment at the crossroads: Elections in a conflict-troubled biodiversity hotspot. Environmental Science & Policy, 135, 77-85. Check here.

[3]

Samper, J. A., & Krause, T. (2024). “We fight to the end”: On the violence against social leaders and territorial defenders during the post-peace agreement period and its political ecological implications in the Putumayo, Colombia. World Development, 177, 106559. Check here.

Bangka Belitung and West Kalimantan

a) Palm Oil

In the global commodity chain of palm oil, Indonesia is one of the biggest producers of the commodity. According to an official report of the Government of Indonesia, the palm oil production accounted for 48,68 million tonnes and provided about 16 million jobs while supporting the national economy that shared up to USD 18 million from the total export in 2018. An official report released by the Minister of Agriculture of Indonesia, stated that the total number of palm oil cover accounted for 16,38 million hectares in 2019. In this report, West Kalimantan becomes the third largest area with oil palm cover in Indonesia with a total area of 1.80 million hectares, while the largest area of oil palm cover is in Riau with 3.38 million hectares and followed by North Sumatra with a cover area of 2.08 million hectares.

However, the demerit of producing palm oil commodities has outweighed its benefit not only for the communities on the ground but also the environment. Our visit in Pontianak, West Kalimantan, one of the regions in Indonesia which produce palm oil and has huge palm oil plantation areas, found that the increasing number of palm oil plantations has caused massive land-use changes while decreasing forest area in the region. According to Mongabay, an environmental news agency, the number of forest areas in West Kalimantan has decreased 1,25 million hectares between 2002 and 2020, citing the Global Forest Watch report. Nonetheless, referring to Global Forest Watch in the same news article, the report stated that the loss of tree cover was not necessarily a deforestation, or solely due to land expansion for oil palm plantations. For instance, it can be related to natural conditions such as storms, epidemics or forest fires.

Moreover, the palm oil expansion in Indonesia has increased the public debate about ecological issues since in the early 2000s, particularly on the biodiversity loss. A study reports that palm oil expansion which enabled deforestation in early 2000 has threatened or even diminished endemic flora and fauna population richness in West Kalimantan. One of them, which has attracted the attention of many scientists, is the case of the death of more than hundreds of thousands of bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus), one of the many endemic animals in Kalimantan Island (Borneo). A study clearly mentions that elimination of many orangutans’ is due to the land use change (deforestation) for industrial-scale oil palm plantations and logging activities for fulfilling the needs of the pulp and paper industry.

The expansion of palm oil plantations has also raised an issue about agrarian change into monoculture. The monoculture pattern driven by industrial-scale palm oil plantations has threatened the bird species’ richness in West Kalimantan. A study recorded that the palm oil plantations become the most avoided vegetations area by flock of birds, which can put many species in jeopardy. This certainly contributes to the loss of the richness of bird species in this region. Furthermore, many of these industrial plantations claimed to be sustainable through standardization schemes (for example, RSPO), in fact not all of them have criterias such as the labels have given. Otherwise, expansion of palm oil in industrial scale actually threatens endemic species richness of the West Kalimantan region.

b) Tin

Indonesia is one of the largest tin producers in the world. The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources indicated that Indonesia has the second largest reserve estimated at 800.000 tons and second largest producers of tin in the world. The tin contained in rocks and soil is estimated to be much higher, reaching 0,693 pounds per cubic tons yard compared to Malaysia, citing a survey by USGS in 1969. Almost all tin mining in Indonesia is produced in Bangka and Belitung islands which has been a tin mining location since the Dutch colonialism era. It is understandable because the Bangka Belitung Province is part of a tin belt area in the Southeast Asia region that stretches from Myanmar to Indonesia.

The production and management of tin commodities in Indonesia may be described as highly centralised with the state-owned enterprise which is PT Timah being the largest producer. The company has 473.388 hectares in total of mining areas with 127 mining business permits/IUPs that spread from 184.672 hectares offshore and 288.716 hectares on shore. According to the International Tin Association, in 2022 PT Timah produced 19.800 tons that decreased 25,3 % than 2021 which produced 26.000 tons, which may be affected by the export banning policy (downstream/kebijakan hilirisasi). However, the private sectors are also involved in extracting and processing by establishing smelters and owning mining areas.

The EPICC Indonesia’s team visit to Bangka and Belitung island found that it could be said that mainly of the communities in the region relied their livelihood on tin. Apart from the attractive price in the market, the mining for tin ore can also be done easily by the locals utilising rudimentary tools. Unfortunately, the practice of tin mining in Bangka Belitung has been widely condemned because it has negative impacts on the environment and is always associated with social problems. For instance, the immense void (ex-mining holes) which is caused by non-enforcement of post-mining reclamation policy. Environmental degradation has also expanded not only on the land but also on the sea, because shifts in mining area due to tin depletion onshore. Moreover, expanded mining to offshore has also increased tension of conflict between communities.

During the EPICC Indonesia’s team visit to Bangka and engage with the local fisherman, the offshore mining becomes a threat to marine life and coral reefs, particularly due to offshore mining activities. The offshore tin mining is destructive as it commonly uses big suction vessels and dredgers for industrial mining, and hundreds of pontoons built by the artisanal miners. A fisherman that we interviewed informed us that there has been a decline in the number of fish caught regarding the number and its variety, and many of the fishermen have to go further out to catch fish. The EPICC Indonesia’s observation also discovered that the sea and the catchment areas for the fish have turned into murky water because of the suction process in tin mining.

Further, there are many studies and gray literature that report about tin mining’s effect on biodiversity. For example, a study found that the tin mining extraction in Bangka and Belitung has threatened the density of mangrove that is crucial for coastal areas as an island. Tin mining is also reported to have endangered the existence of Arowana Kelesak, an endemic freshwater species. In addition, the mining has damaged the soil in Bangka Belitung ranging from deterioration of soil structures to loss of soil organic matter and its fertility. The offshore mining also denounced the sedimentation downstream of the river and lost vegetation leading to endangering coral reefs in Tanjung Pandan.

EU Deforestation-free regulation (EUDR)

The EUDR as a perverse connection?

In the attempt to better and critically understand the connections between EU as a territory of consumption and the territories of extraction, the EPICC group decided to focus on the European Union Deforestation Free Regulation (EUDR) as a recent example of public-private governance intervention where power and links are traced and territorial dynamics are changed by decisions made far down the chain, namely in the European regulatory, political and socio-economic space. This choice fits with EPICC’s intention to identify and analyze leverage points (chokepoints) and blind spots, and sheds light on the micro and macro conditions that may facilitate the mitigation of environmental and social impacts that occur at the selected locations of extraction and production (in Brazil, Colombia and Indonesia).

The blog series available on our website results from over a year of research conducted by EPICC researchers, and in particular from sixteen semi-structured interviews with multi stakeholders directly engaged in the EUDR, its conceptualisation, and the political process around it. These interviews were carried out over a four-month period, coinciding with the European Union (EU) level trilogue negotiations and the adoption of the new EUDR. Each interview lasted approximately one hour and was conducted through virtual platforms. They aimed at gathering data and investigating ongoing policy and narrative changes through the voices and experiences of the actors who were and are directly involved in the promotion, discussion and definition of the regulation.

The researchers have aimed at combining multiple perspectives and voices. Although some difficulties were encountered in the outreach process, such as the decline of interviews by several prominent actors within the EU, the process still provided valuable insights into the level of engagement and willingness by those actors to participate in discussions related to the EUDR. In total, the research involved five interviews with individuals from non-governmental and civil society organizations, five interviews with EU public actors, three interviews with country missions to the EU, and three interviews with private sector actors (comprising two from prominent certification schemes and one from a retail sector association). These various viewpoints contributed to a more comprehensive understanding of the implementation process and helped identify key elements in this ongoing process.

Through this series of short publications, we aim to provide our contribution to the multiple discussions that are taking place with regards to the unpacking of the regulation and its implementation. In contrast to other debates, our focus however extends beyond practicalities and technical details: we embed the EUDR in the complexity of historical and political-ecological processes that unfold in the territories of production, and enquire on the potential and limitations that come with the European intervention.

The first blog provides an overall and critical overview of the EUDR as a recent and legally innovative intervention in the governance of global agri-food chains. In the text, we highlight the main procedural and substantive elements of the Regulation, so as to facilitate the understanding of ongoing conversations within and outside academia. At the same time, we sketch the scope of the critical interventions contained in the following blogs and that concern the background of the regulation, its procedural requirements, the substantive notions adopted and its implementation.

The second blog enters into the details of the EUDR as an ‘ecological regulation’, i.e. a piece of law that will have implications and consequences on both social and environmental processes and practices in the countries of origin of the seven covered commodities. Through the notion of ‘shift’ we suggest that the regulation, although it does not prescribe any behavior outside of the EU borders, will create the positive and negative incentives for five shifts that are likely to take place: a shift from export/production to the EU market to other markets that do not regulate deforestation in a similar way; a shift of deforestation to other ecosystems that are not currently covered under the deforestation-free definition but that may be covered in the future; a shift to other commodities not covered under the scope of the regulation, but that may be covered in the future; a shift in land ownership and an intensification of concentration; and a shift from production for local food security/food autonomy towards the production of cash crops for the European market.