GOVERNANCE & PERVERSE CONNECTIONS

Tapajós Region, Brazil

Soy

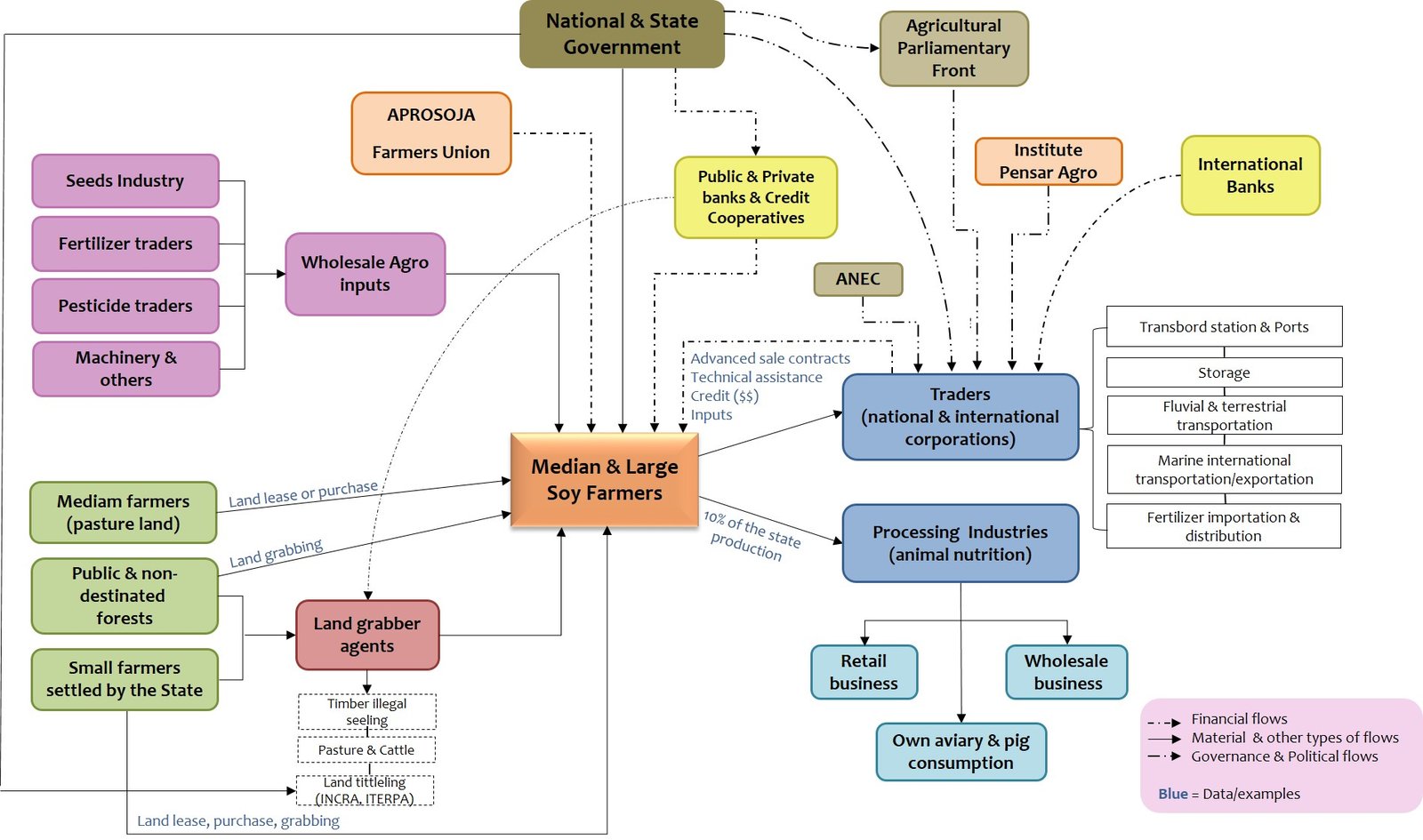

The soybean production, storing and transportation process in the Tapajós Region is permeated by a large range of stakeholders that represent power groups operating at different levels. However, prior to production, other stakeholders directly or indirectly involved in the next stages of the chain also play an important role in promoting soy monoculture in the Tapajós. These stakeholders acting in the previous stages of production are responsible for guaranteeing land availability for farmers and transnational corporations for soybean production and related infrastructure implementation for exportation.

Different ways of making land available include: a) medium to large farmers that used the land for other purposes as cattle production, sell their land for soybean farmers; b) smallholder farmers settled or not by the state lease their lands for medium and large soybean farmers so they can expand their production; c) land grabbers, usually financed by large farmers and other powerful actors, invade public forest lands, promote deforestation, sell the wood, plant pasture and start the process consolidated land regularization with local and regional government institutions. Through this last process illegal is transformed into legal, and soybean enters in the chain of commodities produced in the Tapajós Region substituting directly or indirectly forest remnants (Figure 1). While land with forest cover costs approximately US $70.00, the same hectare with pasture varies between US $400 and US $1,000 (Torres et al, 2017).

With the land, other stakeholders begin to act in the chain. Large input companies (seeds, fertilizers, machinery, etc.) have technicians who support medium and large farmers who are about to start production. However, in the southwestern of Pará (Tapajós Region), a large part of the inputs and seeds are made available by trading companies of the soybean sector, in the form of private credit (Matos et al., 2016, IPAM, 2019). Besides credit, large trading corporations make advanced contracts ensuring the purchase of production, providing inputs, seeds and the storing and transportation of the production.

In the Tapajós region less than 10% of the production goes to processing industries, which is the case for most of the soybean produced in the Brazilian Savannah (Cerrado). Crushing industries and refineries are not present in the region.

The trading corporations have a strong relation with private category associations such as the National Cereal Exporters Association (ANEC) and the Association of Soybean and Corn Producers (APROSOJA) exerting strong political influence in subnational and national governments. The last one, APROSOJA, congregates median and large farmers soybean producers of Brazil and have representation offices and technicians working in the large centers of soybean production in Cuiabá, Sinop and São Lucas do Rio Verde in Mato Grosso. Other stakeholders exerting political influence in the soybean chain include the Instituto Pensar Agro (IPA) and the Agricultural Parliamentary Front.

The Agricultural Parliament Front is a multi-party bloc that works in the National Congress lobbying and drafting rules that favor agribusiness, while the IPA is the strategic nucleus where the FPA’s official positions are built, negotiated and defined (Pompeia, 2022). The growing political power of the Agricultural Parliament Front supported by the IPA is considered as one of the main pushing factors influencing deforestation and carbon emissions in Brazil in the last decade (Pereira & Viola, 2019).

Finally, other crucial stakeholders are the financing institutions, which are pumping money to large corporations related to soy production and exportation, as well as corporations producing inputs (pesticides and fertilizers) for commodities production. According to Forest & Finance, from 2016 to 2023 US$ 307 billion in credit was loaned by banks to corporations operating production, transportation and exportation of commodities, including soybean, produced in the world’s tropical belt regions. Banks are not offering credit alone, institutional investors have also played an important role in commodities operating corporations globally, helding in the same period US$ 38 billion in shares and bonds for the sector. Rabobank and BNP Paribas were responsible for the largest amounts of credit made available for soybean corporations globally.

Gold

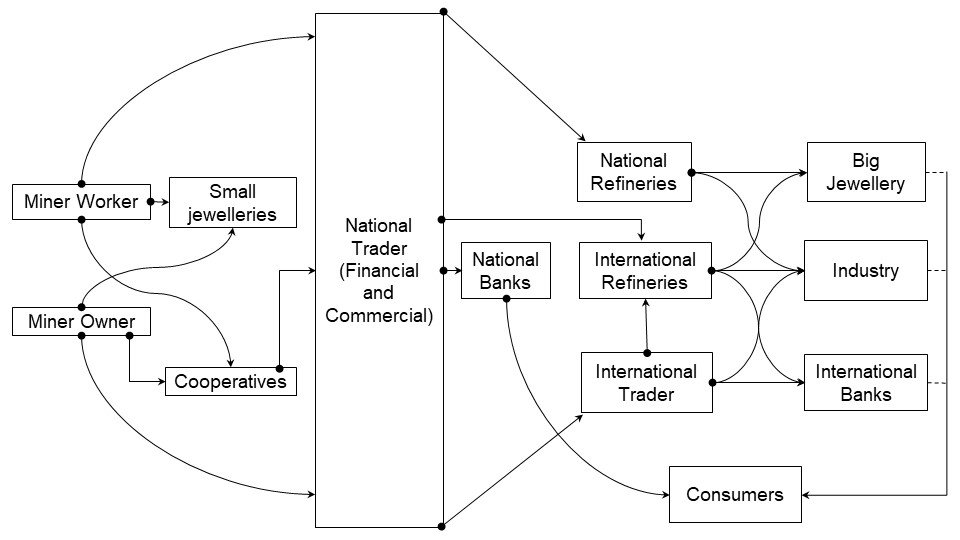

The gold supply in the Tapajós Region has its initial flows in the city of Itaituba, in the state of Pará. The figure below shows the flow of the gold extracted by miners in the region to its final destination on the financial market, in jewelry stores or the medical and electronics industries in Brazil and Europe.

In the Brazilian gold supply chain, miners can be of different types. They can be workers, owners, or be organized in cooperatives. Workers are percentage-paid workers or fixed-income workers in the extraction or infrastructure processes. Both are informal workers in precarious working conditions, including situations of modern slave labor. Miners can also be owners of the pit and the machines, many of them illegal or informal. Cooperatives are formed by one or more mine and machine owners and are also often illegal or informal.

Jewelers can be small jewelers for the local market or international and transnational big jewelry. Small local jewelers typically use a residual volume of gold, whereas transnational companies are significant consumers in the global market.

National traders serve as intermediaries in the financial system, acquiring gold from miners through local gold shops. These traders then sell the gold to international traders who exported from Brazil.

They also sell to refineries, which can be national or international companies, as well as banks, engage in purchasing gold, and negotiate within the national and international financial systems. Manufacturers also play a role in utilizing gold to produce electronics and medical products.

Both international and national consumers contribute to the demand for industrial and medical products containing gold, and some may also invest in gold bars. This intricate network illustrates the diverse players involved in the gold supply chain, spanning from local miners to international investors and consumers.

Putumayo, Colombia

Cattle and Leather

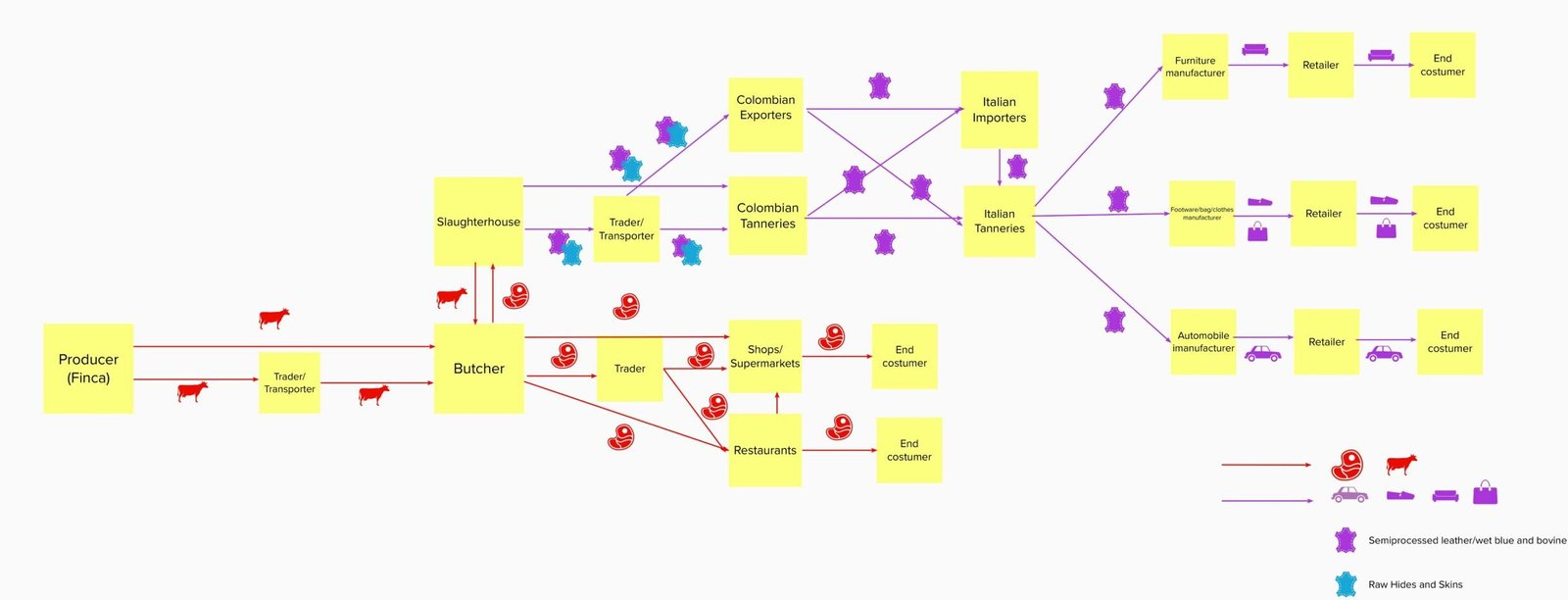

In the cattle and leather supply chain, producers vary based on factors such as the cattle’s life stage, farm size, and production goals. The primary life stages include breeding, raising, dual purpose (combination of breeding and raising), fattening, and complete cycle (breeding, raising, fattening). Livestock not falling into the complete cycle category may be moved between farms, potentially leading to unmonitored and illegal operations. Farms range from small-scale with as few as 10 animals to large-scale with up to 10,000. Production goals can range from a principal occupation to a side business, subsistence farming, or a hobby/leisure activity.

Traders/transporters handle the movement of cattle to markets, new owners, butchers, or from butchers to shops/restaurants. Butchers may be local or part of industrial meat manufacturing. Slaughterhouses, whether private or public-private, offer animal slaughtering services. However, local slaughterhouses often fail to meet hygiene standards, leading to illegal, clandestine activities. Shops, supermarkets, and restaurants come in various sizes, catering to end consumers who consume meat.

In the leather segment, traders/transporters move leather from slaughterhouses to tanneries or exporters. Colombian tanneries are typically family-run, small to medium-sized operations around Bogotá or Medellín. Italian tanneries are also small, employing up to 40 people in four regional districts. Manufacturers of furniture, footwear, bags, and clothing vary in size, offering diverse products in the market.

Gold

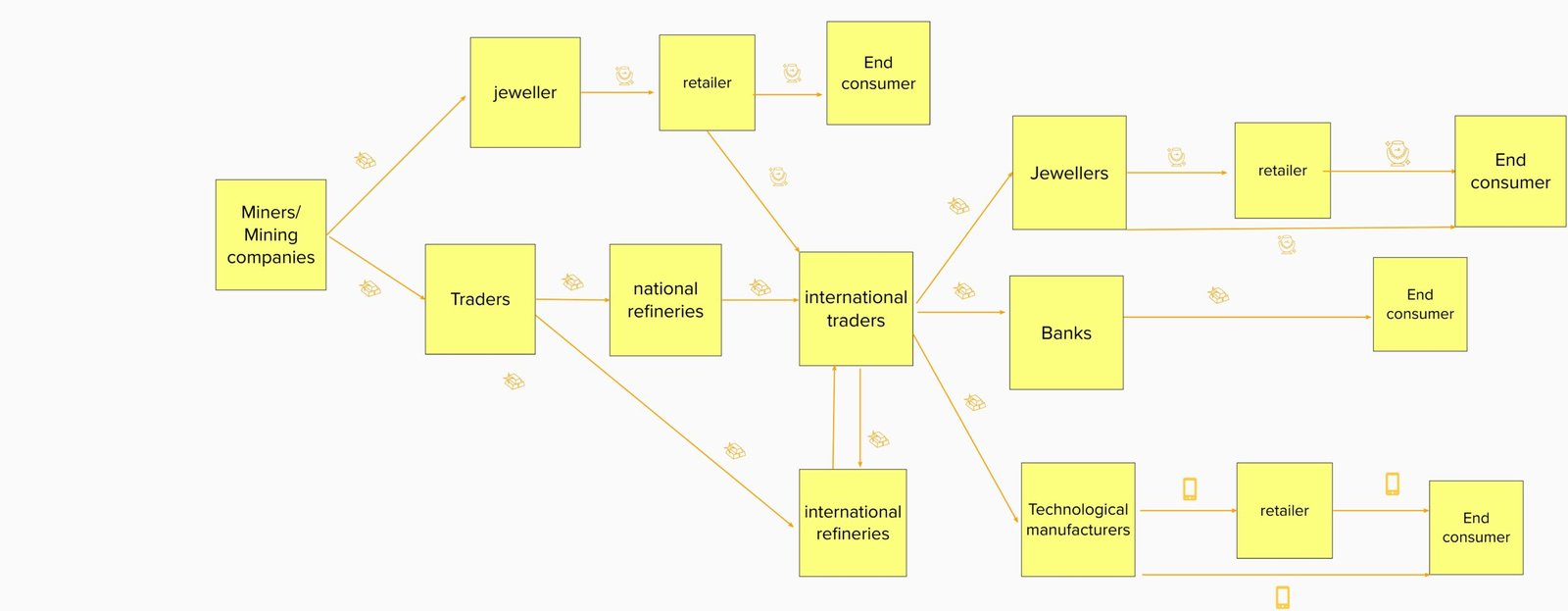

In the gold supply chain, a diverse range of actors follows a similar pattern. At the outset, miners or mining companies exhibit variation based on the quantity of gold extracted, classified as small-, medium-, and large-scale mining. Small-scale permits extraction up to 15,000 tons annually for underground operations and 250,000 cubic meters for open-pit operations. Medium-scale allows up to 300,000 tons for underground and 1.3 million cubic meters for open-pit, while large-scale permits more than 300,000 tons yearly. The size of the business/organization ranges from individual miners to family groups to international large-scale companies.

Small and medium-scale mining is prevalent along the Putumayo river, as large-scale companies are absent due to territorial control by armed groups, limiting investigation. Miners may also engage in subsistence mining, involving individual extraction for generating personal income. Artisanal mining (barequeo) involves non-mechanized sand washing to separate precious metals and gemstones, like gold, without the need for a license. Traders purchase and transport gold from miners to refineries, jewelers, banks, or tech companies. Some miners, facing risks, transport gold themselves to the initial selling point. Refineries prepare gold for further processing.

Manufacturers, including goldsmiths/jewelers, technical manufacturers, or banks, vary in size. Distinctions exist among jewelers who craft, jewel designers who may manufacture, and jewelers selling ready-made pieces. Retailers sell final products to end consumers without involvement in manufacturing, and end consumers are those purchasing products containing gold.

Bangka Belitung and Western Kalimantan, Indonesia

Tin

In the commodity chain of Indonesia’s tin, stakeholders are usually categorized into three major activities, those are mining, refining, and trading. Mining covers the upstream-extraction activities of tin ore, while refining represents the midstream activities that involve selling and transporting tin ores to the refinery and smelter companies that will process the ores to a higher purity value. Trading, on the other hand, covers the activities of verifying the quality of tin ingots that will be traded in the exchange platform to domestic and international buyers.

Mining involves actors with and without mining permits (Izin Usaha Pertambangan/IUP) issued by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of Indonesia. An industrial-scale extractions are conducted by the holders of mining permits, both PT Timah Tbk. as a state-owned company and the private one, who have the legal rights to mine tin ores within their designated concession areas. Meanwhile, small-scale extractions are mainly conducted by (1) independent miners who will mine the ores at any place possible and sell their tin to collectors, or (2) miners that are associated with CVs and mine the ores in particular concession areas of a smelting company.

The role of collectors and CVs are central to bridge the independent, small-scale miners to bigger smelting companies as they have sufficient network, capital, and infrastructure to transport the commodity. Collectors are usually individuals or small groups of people who buy tin from independent miners and pay them directly. Meanwhile, CVs are small, registered entities who are in partnership with smelting companies and obtain a letter of assignment (Surat Perintah Kerja/SPK) from the companies to carry out mining in their concession area and sell the tin to them accordingly, usually at a relatively lower price. Collectors have no formal permits and eventually tend to sell the ores to CVs. The work of both collectors and CVs are typically made possible by the support from capital owners who lend them money to cover daily operational costs of obtaining the tin.

Refining and smelting usually involve state-owned and private companies who are being granted export permits by the Ministry of Trade of Indonesia and are allowed to refine the tin for that purpose. They are given a certain annual quota for export that they cannot exceed. Their main roles are to process the ores to tin ingots with 99,9% purity. For this purpose, these companies have to make sure of their continued supply of ores from their concession areas or CVs that are in partnership with them. They also have to ensure the supply of additional materials required in the making of pure tin ingots, such as coal, limestone, crystallizer, and aluminum. Their work is reviewed regularly by a Competent Person Indonesia (CPI), individuals who are being granted a license as an expert and are responsible for reports on resource estimates, reserve estimates, and exploration results for the company before being granted export permits. The report will be the basis for the government to decide on the annual export quota for the company.

Trading involves stakeholders who work to ensure the quality of tin ingots through the verification process up to the exchanges used by domestic and international buyers to purchase the commodity. Following the production of tin ingots, Sucofindo or Surveyor Indonesia came into frame to verify the origin and quality of the tin. Their main role is to do an inspection and conduct a direct quality check to make sure if tin ingots produced are meeting international standards and the requirements regulated by the national government to be suitable for export, including the minimum purity level outlined in the government’s policy of banning raw materials exports. The process also aims to ensure that buyers would get Indonesian tins that were mined and processed sustainably. Once verified, the ingots will be stamped and transported to the warehouse.

The tin trading is performed by only two exchanges, those are Indonesia Commodity and Derivative Exchange/ICDX (Bursa Komoditas dan Derivatif Indonesia/BKDI) and the Jakarta Futures Exchange (Bursa Berjangka Jakarta/BBJ). Both are significant operators in the physical tin market and in overseeing tin transactions in Indonesia, either for export or domestic purposes. Once the purchase is finalized, the ingots will be delivered to the buyers.