GOVERNANCE & PERVERSE CONNECTIONS

Tapajós Region, Brazil

The Munduruku Women

In the Tapajós Basin, the Munduruku indigenous people, particularly the women, have been bravely resisting the violence and advances of illegal gold mining in their territories. The reactions of resistance range from actions of self-defense to denunciations by public authorities and the media.

Marileusa Munduruku, from the Tapajós Region, is the coordinator of Wakobarun Munduruku Women Association that develops different actions to strengthen the anti-mining movement anti-mining movement, making complaints to the public ministry, holding marches and raising awareness in communities. They develop territorial protection and management actions by creating community strategies for monitoring their territories with drones and other equipment donated by national and international organizations. At the same time, they continue to maintain their traditional practices, producing handicrafts for sale, singing and dancing, raising their children and grandchildren.

Here you can find more about their resistance movements:

- The Munduruku and their strategies for defense of their territory

- As their land claim stalls, Brazil’s Munduruku face pressure from soybean farms

- To fight invaders, Munduruku women wield drone cameras and cellphones

The Munduruku women of the Santareno Plateau, from the açaizal village, have been also fighting to maintain their traditions of producing natural medicines and crafts. In workshops organized by the community, women revive their practices for the production of ointments, tinctures, teas and other medicines, studying the species and forms of production. Teenagers and children are also present in the workshops, who learn the Munduruku traditions from their elders.

The Quilombolas traditional communities

The Lower Amazon region and the Santareno Plateau are home to 12 quilombola communities whose origins are Africans and their enslaved descendants who worked on cattle farms and cocoa, coffee, rice and sugarcane plantations in the 18th century (Acevedo & Castro, 1998 in Rocha et al., 2022). Quilombos were formed following the escape of slaves and later with the arrival of former slaves and their families. Nowadays these 12 communities are organized through the Federation of the Santarém Quilombola Organizations (FOQS). None of the quilombola lands in the region have definitive title to their territories.

In Lake Maicá, 8 quilombola communities have been fighting for their rights to access the Free, Prior and Informed Consent Consultation Process guaranteed by Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO). A series of portuary terminals are planned and in the process of being installed in one of the areas with the greatest aquatic endemism in the lower Amazon Basin.

In September 2020, FOQS made a petition requesting to join as a litisconsorcial assistant in the public civil action against the company Atem’s. Atem’s is an Oil Distribution company aiming at selling oil to the ships harboring at the EMBRAPS port, also with the environmental licensing suspended by the Federal Justice in Pará State. In both cases, FOQs and the non governmental organization Terra de Direitos reported to the Federal and State Public Ministry the illegalities of the projects.

Besides the inconsistencies in the environmental impact studies, the two companies did not carry out the free prior and informed consultation process with the quilombolas communities and the other traditional communities living in Lake Maicá. Both companies continue to have their licenses suspended. The quilombola communities remain attentive and continue to fight against the impacts already felt in the Lake dynamics due to the silting and landfills.

For more information check here:

Ferrogrão Railway and the Indigenous Communities of Mato Grosso and Pará State

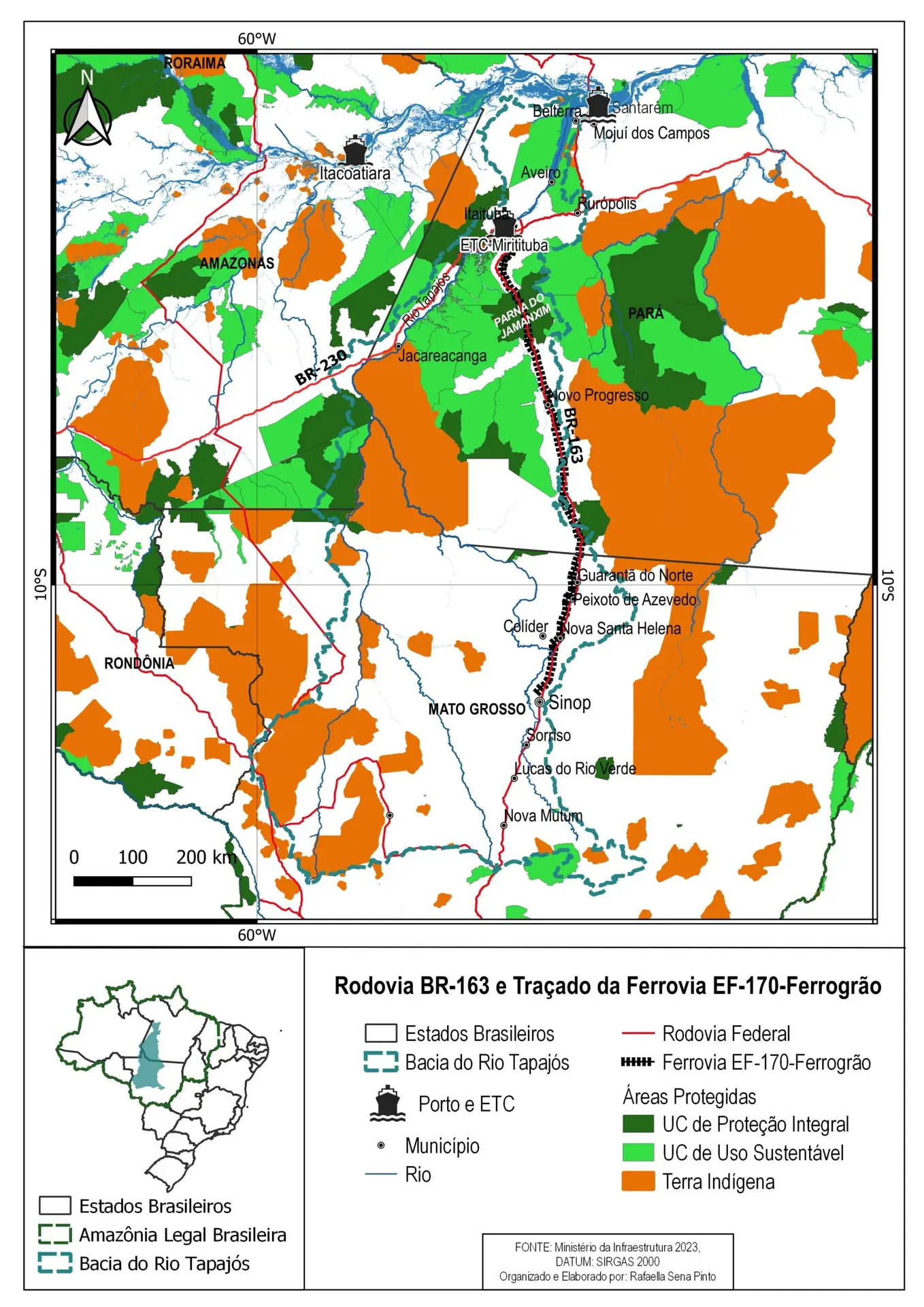

The EF-170 railway, known as Ferrogrão, was presented more than a decade ago by agribusiness multinationals to the federal government. The railway’s proposal is to connect the cities of Sinop, in the north of Mato Grosso, the heart of Brazilian soy production, over 933 km, to Itaituba, located in the southwest of Pará, on the banks of the Tapajós River. In Itaituba there are port terminals controlled by multinational corporations that ship grains mainly to China, Europe and the Middle East. In Itaituba there are five transshipment stations operated by the following corporations: Amaggi and Bunge, Cargill, Cianport, Hidrovias do Brasil S.A. and Transportes Bertolini Ltda.

It is estimated that the railway affects more than 7,300 km² of indigenous lands and at least 48,000 km² of conservation units, and is expected to cause the deforestation of an area of 50,000 km². The route overlaps with 12 communities of the Mẽbêngôkre-Kayapó people who live in the Baú and Menkragnoti indigenous lands, two communities in the Panará TI, in addition to passing through the territories of three isolated peoples: Pu’rô, Isolados do Iriri Novo and Mengra Mrari.

Source: Rafaella Sena (2023).

According to Reporter Brasil (2022), the railway project has been progressing for ten years without proper socio-environmental impact studies and prior consultation with affected communities, violating the principles of Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization. The impact studies carried out disregarded most of the indigenous lands neighboring the railway as affected by the project and have a series of weaknesses.

In September 2023, the Federal Supreme Court suspended the action that judged the constitutionality of the construction of the railway and ordered the development of environmental impact studies and consultation with indigenous peoples and traditional communities affected by the project.

On March 4, 2024, representatives of indigenous peoples, traditional communities, organizations and social movements from Pará and Mato Grosso held a “Popular Court” to judge Ferrogrão and its consequences. The jury’s indictment pointed out a series of rights violations and sentenced the project to be immediately terminated. Among the rights violations listed are:

- failure to carry out communities consultations according to the Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization;

- the fragility of social and environmental impact studies and the lack of assessment of the cumulative effects of other projects;

- disregard for the rights of nature, especially the Amazon and Cerrado biomes;

- disregard the effects of the project planning and licensing process that are already generating land speculation, land grabbing and deforestation.

Putumayo, Colombia

After decades of armed conflict and violence that ripped through Colombia and were particularly severe in the Putumayo region, the last years have offered a glimpse of hope. A collective struggle and mobilization against extractive industries emerged, centered around the identity of the Putumayo as an Andean-Amazonic territory, where the highlands of the Upper Putumayo are ecologically, culturally and spiritually connected to the Mid – and Lower Putumayo. New alternative livelihoods emerge, for instance tourism and novel tree crops grown in agroforestry systems, means that people have more options that allow them to diversify away from traditional and more destructive forms of earning a living. Local small-scale and artisanal miners have started to form associations to obtain legal recognition from the authorities and have started alliances to restore degraded lands and former mining sites. Global conservation NGOs have also entered the picture and provide some support to farmers who seek to diversify their agricultural production and engage in more sustainable agroforestry practices.

Indigenous and civil society alliances further pressure the national government to restrict mining titles and fight for the ecological and cultural integrity of the Andean-Amazon territory. In their struggles these groups also get national and international recognition and support, which allows them to use this media pressure and increasing public scrutiny to turn up the resistance against new mining sites.

Bangka Belitung, Indonesia

Bangka Belitung has been known as the “island of tin” for its richest tin reserves and long history of mining operations, but a considerable part of the community has been living in, engaging with, and experiencing, the island beyond the tin. They reclaim and reimagine the island as a place where their life extended beyond the extractive industry. While the miners community believed mining is tradition that contributes significantly to sustain their livelihood, the anti-mining groups denied that mining has ever been a part of their culture and attributed the practice to migrants from Sumatra and Java instead.

The anti-mining communities, often comprised of indigenous groups, depend on the sea by working as traditional fishers or in plantations as they believe these cause minimal harm to the environment. In addition to the huge corruption case in the mining sector, the communities stand by their ground that both on and offshore mining are deadly for workers and brought about serious damage to local fisheries, mangrove forests, and coral reefs. Organized by a globally-connected NGO, Friends of the Earth, these communities are involved in numerous and latest protests asking the provincial government to issue a moratorium on tin mining licenses and perform a comprehensive evaluation on the ongoing practices.

Miner communities, however, also have hopes. To sustain their livelihood, they wish to be able to mine openly at any time without any fear of raids. They aspire for their ore’s price to be competitive. Some independent miners even hope to work with bigger companies or CVs to make sure they get the security of continuous extraction, but they have to compete with workers from outside the Island or skilled ones to get the job. Being formalized can be among the answers, but they remain in a disadvantaged position as the designated people’s mining areas often overlap with PT Timah’s concession areas. They have no choice other than working with state-owned or private companies to be able to survive, even with less earning and without insurance, healthcare, or adequate working equipment to ensure their safety. For some of them who are not legible by the system or deemed irrelevant for the labor market, they chose to continue the mining in PT Timah’s working areas either independently or with a small group and sell the ores elsewhere.

Although a long-gripped social tension is persistent between communities who believe tin is a blessing and those who are convinced that it is a curse, the story of hope from the islands comes from both of the communities. It is a hope to call Bangka Belitung a home where they could fit in and sustain their everyday life.

West Kalimantan, Indonesia

Indonesia, the world’s largest producer of palm oil, is a prime example of the complex interplay between economic development, environmental sustainability, and social justice. The oil palm industry has brought significant economic benefits to the country. However, its rapid expansion has also raised concerns about deforestation, biodiversity loss and also threatening the survival of endangered species. In addition, the expansion of industrial oil palm plantations has been associated with land conflicts, displacement of indigenous communities. These social issues highlight the need for more equitable and sustainable approaches to oil palm cultivation.

Since the development of the palm oil industry in Indonesia in the late 1980s, conflicts arising from palm oil have also been recorded as continuing to increase. Although there is no official government data describing the existing conflicts, local media reports showed that almost every month there is news regarding conflicts related to palm oil. The conflicts occured not only between communities and companies whose land is grabbed and converted into oil palm plantations, but also between companies and their workers. However, efforts to overcome and prevent similar incidents are also being carried out more intensively by the government and civil society organizations collaborating with scholars.

It then creates a hope that the Indonesia future regarding palm oil could be better. The optimism stems from strengthening grassroots activism which has seemingly become a watchdog for the powerholders and companies that continually utilized jurisdictional approaches to encourage a new regulatory framework to protect smallholders and workers.

The West Kalimantan provincial government, for example, started to develop a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for grievance mechanisms for the agricultural sector to address palm oil conflicts related issues in 2019. Moreover, the West Kalimantan Provincial Government, especially the Plantation and Livestock Agency, is holding a capacity building for the bureaucracy at the street level to improve their knowledge about the importance of the grievance mechanisms for reducing conflict and preventing escalating conflicts quickly.

The prospect also came from scholars that give a lot of attention to the palm oil conflict and try to find a contextual solution that helps the policymakers in measuring the issues.

According to a collaborative study entitled ‘Palm Oil Conflict and Access to Justice in Indonesia’ or POCAJI, it was stated that in the last two decades there were 69 conflicts that occurred between local communities and mega-companies related to the development and management of industrial oil palm plantations. The research is a collaboration between Universitas Andalas, KITLV Leiden, Wageningen University and six different NGOs in Indonesia. This research tries to map types of approaches in resolving palm oil conflicts and also examine the effectiveness of conflict resolution mechanisms in West Kalimantan. You can find more about the POCAJI study here.

A study conducted by Abram, Meijaard, Wilson et al. (2017) has also provided suggestions that mechanisms such as the jurisdictional approach would really help to prevent similar conflicts, such as the Free and Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) could be a game changer. Find the study of Abram, Meijaard, Wilson et al. (2017) here.

Furthermore, movements from below driven by a number of civil society institutions and communities that are affected by the oil palm plantations are robust. They held demonstrations and often even closed road access for the company’s heavy equipment (backhoe or excavator). They even demanded that the people’s representatives institution (DRPD) listen to their disagreements and asked them to put pressure on the central and provincial governments. Not only at the national level, a number of communities that face conflict related to palm oil expansion try to establish a collaboration with a local NGO while utilizing international networks to put pressure on its company and find a resolution that benefits them.

For example, the conflict that occurred between the Dayak Hibun ethnic community in Sanggau, West Kalimantan and PT Mitra Austral Sejahtera (PT MAS). This community submitted a complaint to the RSPO because the company was deemed to have violated a number of principles. See the story of Dayak Hibun conflicts with the company here.