1. Introduction

Each year, the EU imports billions of euros worth of agricultural commodities from multiple countries around the world, in particular in the Global South, and uses a good part of them to become the largest exporter of food commodities in the world. The EU’s economic growth thus relies heavily on extraction processes at the other end of GVCs, as recognised by the new EU deforestation-free products regulation 2023/1115 (EUDR). On the other hand, socio-ecological impacts stemming from the production and circulation of global agricultural commodities are concentrated in the territories where natural resources are extracted. These flows carry ecological, economic, and social implications, beyond industrial and agricultural concerns, that must be highlighted.

The uneven distribution of benefits and consequences of GVCs was key to the elaboration of the EUDR: the idea behind the new regulation is that of addressing the release of greenhouse gases, deforestation and the loss of socio-biological diversity that are associated with EU consumption. In turn, the EU and Member States (MS) are identified as key players in the improvement of the socio-environmental performance of seven agricultural commodities by means of higher standards, transparency and traceability. However, it must be underlined that, while the unilateral provision of environmental and social requirements to trade may reduce the footprint associated with EU consumption, it does not automatically equate to environmental justice. In fact, it could lead to a deceptive sense of ‘socio-environmental comfort’ among EU policymakers, consumers, and corporations, while reproducing forms of ‘socio-environmental sacrifice’ and reinforcing global inequalities.

In this contribution, we understand environmental justice to be a lens to discuss the social and ecological distribution of costs and benefits of environmental measures, and to enquire on the participation of the affected people and on the recognition of their alternative visions and aspirations. (1) This blog specifically seeks to provide an overview into the different dimensions of environmental (in)justice stemming from the EUDR’s intellectual framework, adoption and implementation. Three dimensions of environmental justice are taken into account to develop the analysis: (i) the equitable distribution of socio-environmental burdens and benefits; (ii) procedural justice as the fairness and autonomy of the decision-making process; and (iii) the recognition of the diversity of the participants and experiences reflected across GVCs. In doing so, we underline the need, in David Harvey’s words, to “confront the underlying processes (and their associated power structures, social relations, institutional configurations, discourses, and belief systems) that generate environmental and social injustices.”.

2. Attention to the distribution of environmental burdens and benefits

In order to interrogate the EUDR from an environmental justice perspective, we start by looking into the distribution of benefits, opportunities and risks inherent to the regulation. Specifically, the unequal distribution of environmental harms across territories and social groups is one of the defining elements of environmental injustice. Distributive justice – as originated in the context of Black and Brown communities in the United States in the late 1970s – is here understood as “the distribution of environmental goods and bads among populations” (2), where environmental impacts are deeply intertwined with the lived experiences and histories of communities. Unlike situations where the harm is experienced in the proximity of its source, an environmental justice approach to GVCs, however, allows us to connect commodity flows – including the emissions and deforestation that are ‘embedded’ in traded commodities – with the benefits and burdens along these value chains.

In this regard, Europe has historically been and remains responsible for a disproportionately high share of global environmental destruction and resource consumption. This has been the case throughout the colonial era, but the negative environmental and social costs of European industrialisation and consumption are still constantly transferred to and borne by the regions, countries and territories where extraction and circulation take place. In particular, since the establishment of the sugar plantations in the Americas, the development or reinforcement of agricultural GVCs for European consumption has had significant distributive implications in the territories of production. More than that, Jason W. Moore reminds us that the establishment of GVCs has shaped the territories, their ecologies and the lives there by imposing production and consumption patterns that departed from existing ecologies and dynamics. In this context, if we consider that EU-bound GVCs have been contributing to the unequal distribution of environmental burdens and benefits across the world, one must question whether the EUDR is informed by this pattern and its implications. However, our analysis of the theory of change and procedures of the EUDR leaves no doubt to the failure of the EU to move away from unequal social-ecological exchange at the heart of its consumption patterns, and even less to consider and redress historical uneven development. The following points outline this assertion.

- First, distributive justice comes into play with regards to the introduction of the temporal benchmark (i.e. December 31, 2021) in the regulation. This approach inadvertently benefits countries that have expanded agricultural production by converting natural vegetation, effectively rewarding those with a history of participating in deforestation and forest degradation. This creates a disparity where countries that have significantly contributed to deforestation stand to benefit more from trade opportunities with the EU. Moreover, the EUDR does not make a distinction between different countries and capacities. However, GVCs cannot be considered as uniform, and GVCs interventions cannot be assumed to have homogenous effects across territories and groups of people: territories have very different histories of deforestation, for different commodities, and at different times. In a similar way, injustices occur differently across territories, along with resistance and reaction. (3)

- Second, from the perspective of the territories of production, the EUDR is premised on the persistence of neo-extractivism and the exploitation of natural resources in the way that best fits the consumption patterns and needs of the EU. The surge in global food demand has been and still primarily advantages processing companies, importers, and trading governments, a condition that has led to growing corporate concentration and power in the global food system. This market and land concentration has financial repercussions, but not only: concentrated food systems are often associated with monocultural practices and the integration of territories into global supply chains that feed distant communities (or livestock) rather than local inhabitants. Forms of production and circulation of food have thus a repercussion on socio-economic practices of indigenous peoples, local communities, small-scale farmers, fisherfolks and other social groups that have specific ecological connections with the territories (of extraction). However, rather than rethinking patterns of production and circulation, the EUDR exclusively aims at improving their environmental and social implications, as if the global allocation of value, labour and inputs (water, land, nutrients, etc.) was not a concern per se. Although a change in production patterns may indeed spare EU consumers and industry from using products associated with deforestation that occurred after December 31, 2020, this should not divert the attention from the distributive implications of normalising GVCs.

- Lastly, on the consumer-side, critiques have emerged that the EUDR will likely have negative repercussions on the final price paid by European consumers. The EU is indeed not fully internalising the costs of adapting to the EUDR, primarily due to the limited scope of future programmes and partnerships under the regulation. Although the expectation is that the costs of investments will be borne by the private sector, this does not necessarily translate to EU consumers not facing more expensive products. This scenario has significant distributive implications within Europe, as the burden of higher food prices may disproportionately affect the most economically vulnerable populations. Consequently, this policy could exacerbate inequalities by making better-quality food less accessible to those with lower incomes and, from the way the EUDR is constructed, the latter will not receive any financial support in order to maintain or improve their diets.

3. Procedural justice in the EUDR decision-making process

In the previous contributions to this blog series, we have discussed the EUDR as a unilateral (EU) decision, with cross-boundaries and multi-scalar repercussions. However, does the EU’s ‘good intentions’ (considering all caveats discussed earlier) justify the adoption of this unilateral measure? And what are the implications of its unilateral nature on both its conception and implementation practices? The EUDR specifically followed the usual procedure for EU legislation: stakeholders engagements – including an open public consultation and targeted stakeholder, consultations (interviews and focus groups) – were conducted in the period preceding the adoption of the regulation with the primary goal of ensuring the “identification of all pertinent stakeholders and provide them with the chance to participate in consultation activities to collect their opinions on additional measures that the EU should adopt.” (4) Despite the valuable purpose, and because the EUDR is a regulation with potential global and uneven implications, the pursued stakeholders engagements and consultation processes give rise to several procedural inequalities. Procedural justice here specifically brings the focus to the decision-making processes and the importance of recognition of excluded or marginalised groups.

- First, the impact assessment recognised that the regulation would have implications outside of the EU and that “the poorest and most marginal segments of society, such as smallholder farmers, indigenous and local communities, are disproportionately impacted by the effects of deforestation and forest degradation”. The principles of participatory justice require that, at least, decisions that unilaterally impact and shape territories should not be made without the active involvement and understanding of the affected communities. Yet, an analysis of stakeholder engagement activities reveals gaps in addressing the diverse realities and voices affected by deforestation. For example, from a participatory and legitimacy standpoint, the characterisation of the open public consultation as ‘the largest’ citizen petition for a new EU law is contested. This is due to both the format of the questionnaire (i.e., pre-filled questionnaires distributed by EU-based NGOs) and its content (i.e., participation in a consultation with a predefined scope). The consultation therefore presents the ‘deforestation problem’ in one particular way, while leaving no spaces for other possible interpretations, as highlighted in our initial blog article on the EUDR. Moreover, despite civil society and indigenous peoples’ continuous rejection of free trade agreements (FTAs), such as the EU-Mercosur Agreement, the adoption of the EUDR ultimately reinforces the push for an export-oriented, even more industrial, production model at the expense of other modes of production.

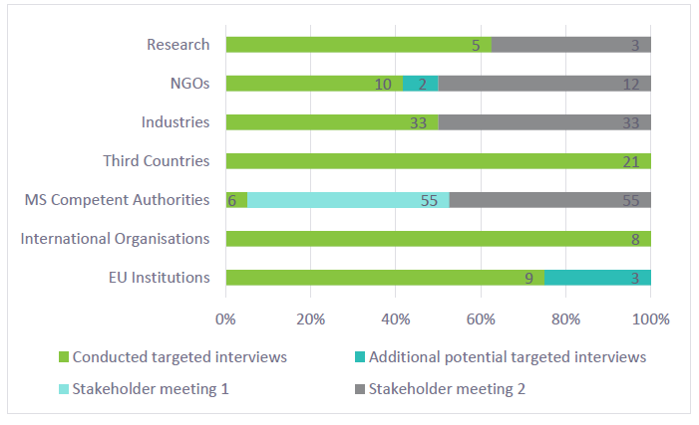

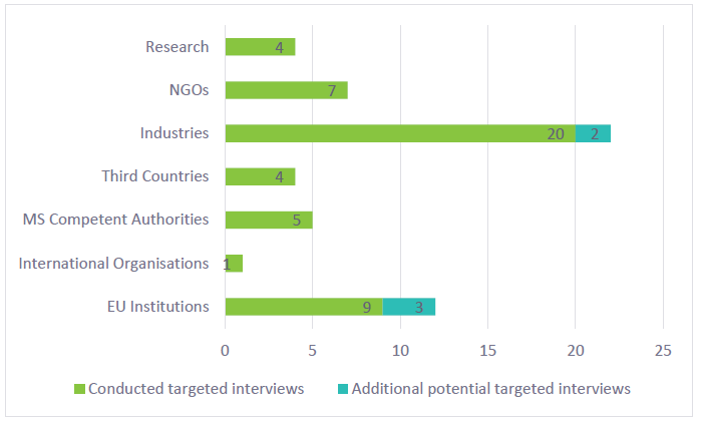

- Second, interactions and discussions with representatives of partner countries and private sector associations have been cited by EU actors interviewed as evidence of participation in the decision-making process. Yet, governments may not necessarily reflect the perspectives of all social groups, including indigenous peoples and local communities in territories. Similarly, the efforts of the EU towards ‘sustainable’ trade and ‘deforestation-free’ supply chains should not go hand-in-hand with an exclusive focus on global commodity producers, but should be opened to actors who are not already involved in GVCs but are impacted by them or may be included/excluded in the future. This was not the case, as powerful economic actors and their representatives appear to have spent considerable time and space with EU actors involved in the legislative process. For instance, the synopsis report of stakeholders consultation activities conducted as a background to the EUDR underlined that most stakeholder consultations involved “civil society and NGOs, European Institutions, international organisations, third countries, Member States competent authorities, industries, and researchers”. However, a closer examination reveals that targeted consultations, including interviews and stakeholder meetings, were predominantly conducted with private sector actors and EU MS competent authorities (see. Figures 1 and 2). This raises concerns about the inclusivity of the process and prompts questions about the extent to which other voices were afforded adequate space and representation. Furthermore, the role of multi-stakeholder platforms in prioritising the interests of sectoral and bureaucratic actors, often excluding vulnerable groups, is well-documented in existing scholarship. (5) Relying on these mechanisms as participatory processes raises significant procedural and recognitive justice concerns.

The regulation hence falls short in addressing how participation could have been facilitated, including in the definition of the underlying theory of change and objectives, and it does not confront the power imbalances between on the one hand groups and companies exploiting resources and on the other hand local populations. Future engagement with different stakeholders have been promised by the EU, including the establishment of two working groups (a ‘traceability group’ and a ‘smallholder inclusion group’) to assist the multi-stakeholder platforms in gathering information to interpret and facilitate the implementation of the EUDR. These future engagement efforts present challenges akin to those faced in the previous stages of the process, but also generally found in broader environmental and land governance processes.

4. Recognition of rights, power, and cultural differences across territories

Environmental justice movements have long been active in initiating debates about systemic changes of the dominant production model, acknowledging different voices, diverse ways of life and production intricately connected to territories and natural resources. Recognitive environmental injustices in particular arise when “governance spaces are driven by dominant forms of knowledge and value, which in turn shape both problem analysis and solutions in ways that reflect and reproduce colonial power asymmetries and reinforce social distance”. (6) In fact, the recognition of different groups, value systems, histories and rights is essential in understanding the root causes of deforestation and forest degradation in territories of extraction and production. It is particularly important to acknowledge the diversity of places, histories and culture characteristics, legal frameworks, economic conditions, type of producers, and constellation of relevant actors to understand the way in which GVCs and the expansion of the global agricultural food system have interacted with the localities and have sacrificed lives and ecological dynamics.

We consider that the EUDR, however, failed to open the legislative dialogue (and potentially the future dialogue in the implementation of the regulation) to different modes of living and understanding of territories and food systems, in turn favouring the active promotion of the agri-industrial model, reinforcing power asymmetries and weakening claims by indigenous peoples, local communities and other social groups. The above can be illustrated by the following elements:

- The EUDR embodies a dominant conception of nature (and sustainability), shaping the problem analysis and solutions provided, essentially reproducing epistemic asymmetries and understanding of the society/human dualism that were universalised at the time of Western modernism and colonisation. For example, the choice of an international and common definition of deforestation largely ignores the complexity of the social-ecological relationships that exist around ecosystems in different territories, with the possibility of excluding ecologies that communities would like to be defended or sanctioning ancestral agricultural practices that are based on rotation and periodic slash and burning of the forest. Sustainability, from a political ecology point of view, is not just an environmental objective but a deeply political concept that involves questions of power, justice, and equity.

- The regulation recognises that certification or other third-party verified schemes could be used in the risk assessment procedure by traders and operators (Art. 10). However, certifications produced by actors from within GVCs reinforce recognitive injustices by legitimising large-scale industrial agricultural production and weakens civil society’s political action and social movements. Certifications, moreover, isolate smallholders from markets that require adherence to specific ‘sustainability aspects’ reinforcing existing power asymmetries. On the contrary, communities around the world have developed community-based protocols with regards to the activities that should or should not happen in their territories, and claim their right to self-determination and decision on the future of their territories. The normalisation of GVCs, although ‘greener’, clearly does not go in that direction.

- The ways of life and food systems in territories have been severely affected by the expansion of commodity production, often in association with conflicts over land, expulsion from ancestral territories, increased dependency on global markets, and reduced access to natural resources. Although the regulation mentions the legality of production and indigenous and local community rights, it overlooks the way in which legalities are shaped and challenged on the ground, including by social groups and movements who mobilise for socio-environmental justice and beyond the notion of legality as defined by public authorities and states. By adhering to a Western idea of deforestation, and by relying on traders and operators for the analysis of the legality of production, the EUDR risks to produce its own understanding of legality and to depart from the frictions and turbulences of the territories, with the risk of reinforcing and reproducing legal realities that differ from what the communities claim. One example is the indication of the Brazilian Rural Cadastre as the term of reference for legal ownership in Brazil, the cadastre being the object of historical struggle between dispossessed indigenous communities and large-scale farmers who occupied non-formalised ancestral land and claimed the title.

5. Conclusion

Structural interventions tackling deforestation and biodiversity loss in the dominant food system can bring to light social and environmental injustices. Environmental injustices are, in particular, prominent in contemporary GVCs that connect territories of extraction with territories of consumption. This is particularly the case when we think about the spatial distribution of externalities and value across the agricultural chains covered by the EUDR. GVCs as economic and legislative spaces shaped by the combination of multiple policies and actions are hence privileged stand points to discuss unequal representation and the silencing of certain visions.

Based on our reading of the text and engagement with actors in the EU and in three territories of production, we highlighted that the EU regulatory approach to tackling deforestation and forest degradation does not adequately consider and acknowledge the different rights, powers, and cultural differences in territories along the value chains. We conclude that the regulation is likely to increase environmental injustices across the GVCs and within the territories of extraction, in all aspects of recognition, participation and distribution. This is so because:

- The EUDR overlooks the distributive inequalities inherent in commodity production and their circulation along GVCs, along with EU material responsibilities for a past of deforestation and forest degradation. In this sense, the EUDR perpetuates agricultural supply chains as a complex web of historically rooted food and environmental injustices, while not assuming the responsibility for environmental damages that happened before 31 December 2021, nor the cost of the economic and social transformations that will happen in the territories after the regulation enters into force.

- Systemic failures of recognition of groups of people in territories of production and extraction are at the heart of regulatory interventions by the EU, where – as described above – groups of people are excluded from participation unless they assimilate to dominant worldviews of production model and conceptions of nature.

- The EU agenda on deforestation and biodiversity loss fails to align with the historical agendas, understanding and aspirations of social movements, particularly in response to historical injustices associated with the neo-extractive model. The EUDR is animated by the EU ambition to remain at the centre of global agricultural chains, with no attention to the desires and aspirations of territories and the alternatives that are already practised around the world (e.g. community-based protocols).

When an environmental justice framework is applied, the EUDR seems to hold the potential to amplify instances of injustice and factors contributing to inequalities at the beginning of agricultural GVCs. The EU commitment to reducing global deforestation and forest degradation is certainly laudable, but a more thorough examination of the environmental injustices inherent in this specific form of environmental governance appears needed.